3 questions to ChatGPT. Excluding health & safety in an RF-EMF consultation. Is the Executive above the law or subject to it?

Calling New Zealand-based lawyers with expertise in administrative and constitutional law to critique this response by ChatGPT. (unedited)

PSGRNZ recently sent in a submission response to a current consultation (deadline July 27, 2025) by the Ministry for the Environment (see part 2.5) and the Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment (MBIE) that would amend the NES-TF regulations. These regulations are administered by MBIE (see last line of the regulation text).

We’re interested in how the legal context of a policy and consultation that explicitly drafts out health and safety, when the empowering legislation demands that health and safety is considered - might be communicated.

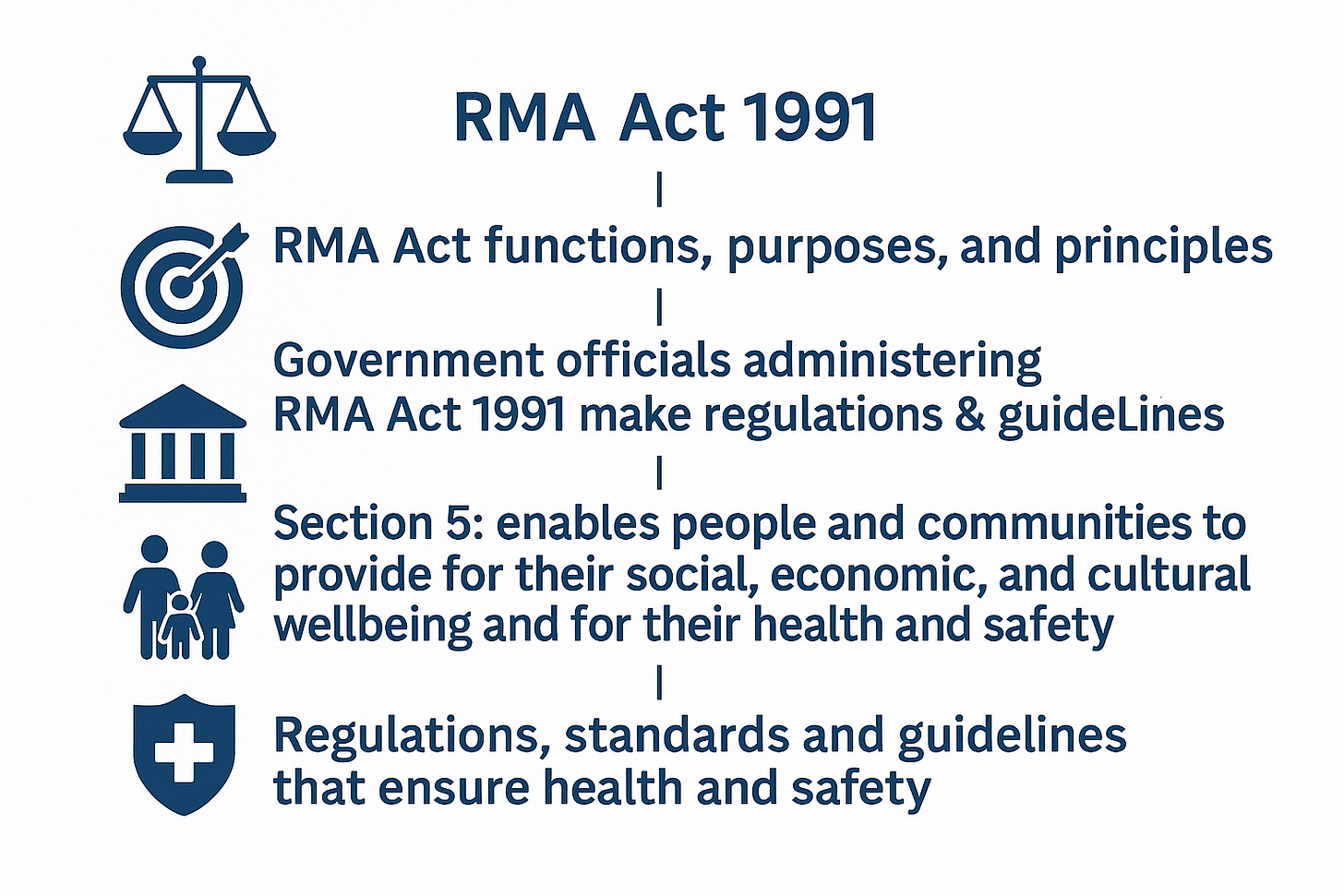

Primary legislation (an Act) provides government officials with the power to make regulations and guidelines under that Act, but in making regulations and guidelines, government officials are subject to the provisions in that particular Act. They are subject to the law.

PSGRNZ asked ChatGPT how this might be communicated:

QUESTION 1

Please explain the legal importance of why regulatory guidelines and standards produced by officials administering an Act of legislation must adhere to the functions, purposes and principles expressed in the empowering legislation, including the resonance of concepts such as 'above the law'. Thank you.

CHATGPT RESPONSE:

Regulatory guidelines and standards issued by officials under an Act of Parliament carry legal significance only to the extent that they are consistent with the enabling legislation—that is, the statute which grants those officials their authority. This requirement is foundational to the rule of law and the legitimacy of public administration in constitutional democracies such as New Zealand, the UK, and Australia. It ensures that regulators are not exercising arbitrary power, but are instead acting as agents of Parliament, whose sovereignty remains supreme in the creation of law.

1. Subordinate Instruments Must Be Rooted in Primary Law

Administrative bodies derive their authority not from inherent power, but from statutory delegation. Legislation provides a framework within which officials may create regulations, standards, or guidelines to implement the law’s intent. However, these instruments are subordinate legislation, and cannot exceed or contradict the statute’s purpose, scope, or principles.

For example, if the purpose clause of an Act focuses on “protecting human health and the environment,” any guideline that sidelines health considerations in favour of economic expediency may be ultra vires (beyond legal power). Such instruments are vulnerable to judicial review and invalidation.

2. Adherence Reinforces Democratic Accountability

Legislative intent—particularly as expressed in a statute’s long title, purposes clause, or interpretive provisions—reflects the deliberative will of Parliament. When officials interpret or apply legislation through regulatory instruments, their fidelity to that intent ensures that the executive does not override or reinterpret Parliament’s role. This protects democratic integrity and guards against bureaucratic or ministerial overreach.

To act otherwise risks a subtle but corrosive shift in power: where unelected officials and technocratic agencies shape law through operational practice, insulated from public scrutiny or electoral correction. In such cases, the executive may come to act as if it is above the law, rather than subject to it.

3. Legal Remedies and the Role of the Courts

Where there is a departure from the statute’s intended purpose, affected parties may challenge the validity of the resulting regulation or decision. Courts can:

Strike down ultra vires regulations;

Issue declarations of inconsistency;

Require decision-makers to reconsider a matter according to law.

This is a vital check in administrative law. It ensures not only that decisions are lawful, but also that regulatory discretion is exercised rationally, proportionately, and for proper purposes.

4. The Rule of Law: No One Above It

The idea that no one—neither Minister nor Ministry—is above the law has deep constitutional roots. It echoes Dicey’s doctrine of the rule of law, and its modern articulation includes:

Legality: Officials must act within legal authority.

Equality before the law: No special exemptions or immunities for regulators.

Access to justice: Citizens must be able to challenge unlawful exercises of power.

If regulators stray from their statutory compass, it is not merely a technical error—it is a breach of constitutional principle. The public service, including regulators, acts on behalf of the Crown but is bound to uphold the law made by Parliament.

In sum, legal and constitutional principles require that all regulatory instruments serve the purpose and values embedded in their authorising statute. This is not a matter of preference or practice—it is essential to upholding public trust, democratic accountability, and the foundational idea that all, including the state, are subject to law.

QUESTION 2

As an example - please explain why the health and safety of people and communities must be accounted for, based on Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Telecommunication Facilities) Regulations 2016 that were made under sections 43 and 43A of the Resource Management Act 1991— (a) on the recommendation of the Minister for the Environment made in accordance with section 44 of that Act. taking into account the function of the Resource Management Act 1991.

CHATGPT RESPONSE:

🧾 1. Legal context: What are NES-TF regulations?

The Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Telecommunication Facilities) Regulations 2016 (NES-TF) are subordinate legislation made under sections 43 and 43A of the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA). These sections empower the making of National Environmental Standards (NES)—which are legally binding regulations that override district and regional rules where inconsistencies exist.

Such standards are not created arbitrarily. The Minister for the Environment may only recommend them in accordance with section 44, which includes consultation and must be consistent with the purpose and principles of the RMA. This connection is key.

⚖️ 2. The Purpose of the RMA (section 5): Health and Safety as a Legal Mandate

Section 5(1) of the RMA sets out its overarching purpose:

“to promote the sustainable management of natural and physical resources.”

And section 5(2) explains what sustainable management means, including:

“sustaining the potential of natural and physical resources (excluding minerals) to meet the reasonably foreseeable needs of future generations; and

safeguarding the life-supporting capacity of air, water, soil, and ecosystems; and

avoiding, remedying, or mitigating any adverse effects of activities on the environment.”

Here, “environment” is legally defined in section 2 to include:

“people and communities, and the social, economic, aesthetic, and cultural conditions which affect the matters stated in this paragraph or which are affected by those matters.”

Thus, the health and safety of people and communities is inseparable from the statutory definition of "environment", and must be considered in all instruments made under the Act—including NES regulations like NES-TF.

🧷 3. Why health and safety must be accounted for in NES-TF

Because:

The NES-TF was made under delegated powers from the RMA, and

The RMA's purpose includes avoiding adverse effects on people, and

Sections 43 and 43A do not override the primary statute—they must give effect to it.

Therefore, any regulation made under sections 43 and 43A—including standards for telecommunication infrastructure—must be consistent with the section 5 purpose of promoting sustainable management inclusive of safeguarding human health.

Neglecting to assess or account for health and safety concerns—particularly non-thermal biological effects, cumulative RF exposure, or vulnerable populations—would risk:

Acting ultra vires (outside the legal scope of the enabling Act),

Failing the precautionary principle (implied via sustainable management and case law),

And undermining public trust in environmental governance.

🔍 4. The role of the Minister for the Environment

Under section 44, the Minister must:

Follow a process of public notification and consultation, and

Ensure the proposed NES serves the purpose of the RMA.

If the Minister recommends regulations that preclude local authorities from considering health effects, or sets standards that are based solely on ICNIRP thermal thresholds, while ignoring wider biological and epidemiological evidence, that could be challenged as:

Inconsistent with section 5 of the RMA,

A failure to exercise discretion for a proper purpose, and

A breach of natural justice if material health risks are excluded from community input.

🧭 In sum:

The NES-TF must adhere to the functions, purposes, and principles of the RMA. Health and safety of people and communities is explicitly part of the legal definition of the environment under the Act. Therefore, regulations made under it must not ignore or render out of scope the consideration of adverse health effects—especially where scientific evidence exists and where local communities are affected.

To do so is not just a policy failure—it may be a legal one.

QUESTION 3

If a policy proposals have rendered out of scope the consideration of adverse health effects - what does this mean in the context of the legislation?

CHATGPT RESPONSE:

If a policy proposal—or a regulatory instrument like the NES for Telecommunication Facilities (NES-TF)—renders out of scope the consideration of adverse health effects, it raises a serious legal and constitutional concern. In the context of the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA), this exclusion could be unlawful, or at minimum, legally questionable.

Here’s why:

⚖️ 1. Statutory Purpose Cannot Be Sidestepped

The purpose of the RMA in section 5 is clear:

“…to promote the sustainable management of natural and physical resources…”

which includes:

safeguarding life-supporting capacity of ecosystems, and

“avoiding, remedying, or mitigating any adverse effects of activities on the environment.”

Importantly, the RMA defines “environment” to include:

“people and communities, and the social, economic, aesthetic, and cultural conditions which affect or are affected by those matters.”

Thus, adverse health effects are inherently part of the statutory concept of “adverse effects on the environment”.

If a regulation or policy proposal declares that such effects are “out of scope,” it:

conflicts with the enabling legislation’s purpose, and

misconstrues the lawful meaning of "effects" under the Act.

🚫 2. Exclusion May Be Ultra Vires (Beyond Legal Power)

Any decision to exclude human health effects from consideration in the development or application of regulations under the RMA:

Must still be justified within the four corners of the statute, and

Cannot arbitrarily or systematically exclude categories of effects that the Act expressly contemplates.

If officials or Ministers promote policies that disable local authorities from assessing health impacts of telecommunication infrastructure—even where those impacts are raised by affected communities—this may constitute an ultra vires exercise of delegated authority, especially if such exclusion frustrates the Act’s purpose.

🧷 3. Breach of Proper Purpose Doctrine

Administrative powers, even when broad, must be exercised for the purpose for which they were granted. This is a foundational principle of administrative law.

If the true purpose of excluding health from scope is to:

shield infrastructure rollout from challenge, or

align with industry standards rather than the statutory definition of environmental effects,

then this raises legal vulnerability under the “improper purpose” doctrine. Courts have previously found decision-makers liable where discretion was used to advance administrative efficiency at the expense of statutory purpose.

📜 4. Inconsistency with Treaty, Rights, and Principles of Natural Justice

The RMA’s administration must also be informed by:

The Treaty of Waitangi principles under section 8, including partnership, active protection, and redress.

Principles of natural justice, particularly for affected persons to be heard on matters affecting health and wellbeing.

Rendering health effects out of scope may amount to procedural unfairness, especially where exposure disproportionately affects children, Māori communities, or other groups with legitimate health and environmental concerns.

🧭 Summary

If a policy under the RMA renders adverse health effects “out of scope”:

It misinterprets the statutory definition of "adverse effects" and "environment".

It may be ultra vires—a use of power not authorised by the Act.

It may defeat the purpose of the RMA, violating the proper purpose doctrine.

It may breach natural justice, the principles of the Treaty, or even attract judicial review.

Such exclusions are not just technical oversights—they go to the heart of lawful environmental governance and the public's ability to participate in decisions that affect their health and safety.

END.

Feedback welcome!