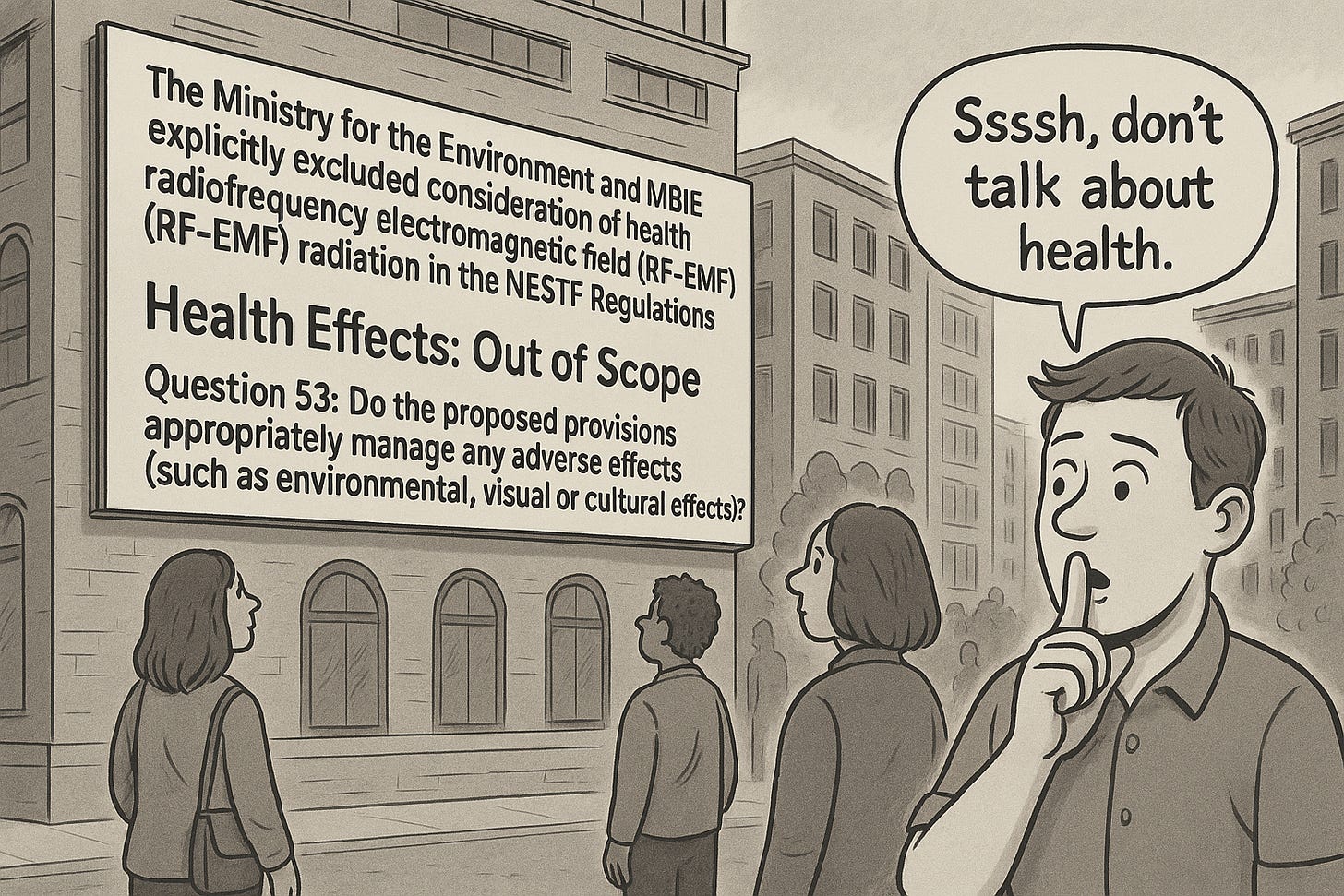

Current MBIE/MftE Consultation Explicitly Drafts Out Concern to Human Health.

The Ministry for the Environment & MBIE explicitly excluded consideration of health effects from radiofrequency electromagnetic field (RF-EMF) radiation in the consultation. Deadline 27 June 2025.

Consultation is currently open to loosen regulations on telecommunications infrastructure. The Ministry for the Environment (MftE) to amend the Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Telecommunication Facilities) Regulations 2016.[1] (Hereafter referred to as NESTF Regs 2016).

An Interim Regulatory Impact Statement proposing the deregulation of the NESTF Regs 2016 was finalised April 16, 2025, a Package 1 Discussion Document was released in May 2025 with a corresponding Attachment 1.5. The proposing Ministers are Hon Chris Bishop, Minister Responsible for RMA Reform and Minister for Infrastructure. Hon Paul Goldsmith, Minister for Media and Communication.

Consultation closes on 27 July 2025.

At the end of the document, we publish our thoughts on answers to questions. As PSGR emphasises, the NESTF Regs 2016 proposal would substantially weaken restrictions – but any public questioning of the safety of such an action has been ruled out of scope.

The Interim Regulatory Impact Statement and the proposals in the Discussion Document (Part 2.5) propose significant and extensive deregulatory status for a broad group of technical devices which emit Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields (RF-EMF). MBIE and the MftE propose to remove authority from regions and communities to decide on the appropriate location of these devices and they propose to expand the category definition and sweep other devices inside this category.

PSGR RECOMMENDATIONS:

PSGR recommends that the proposals are not accepted. Relevant Consultation questions are listed at the end of the document. The arguments supporting the proposal are weak and exclusively revolve around administrative costs.

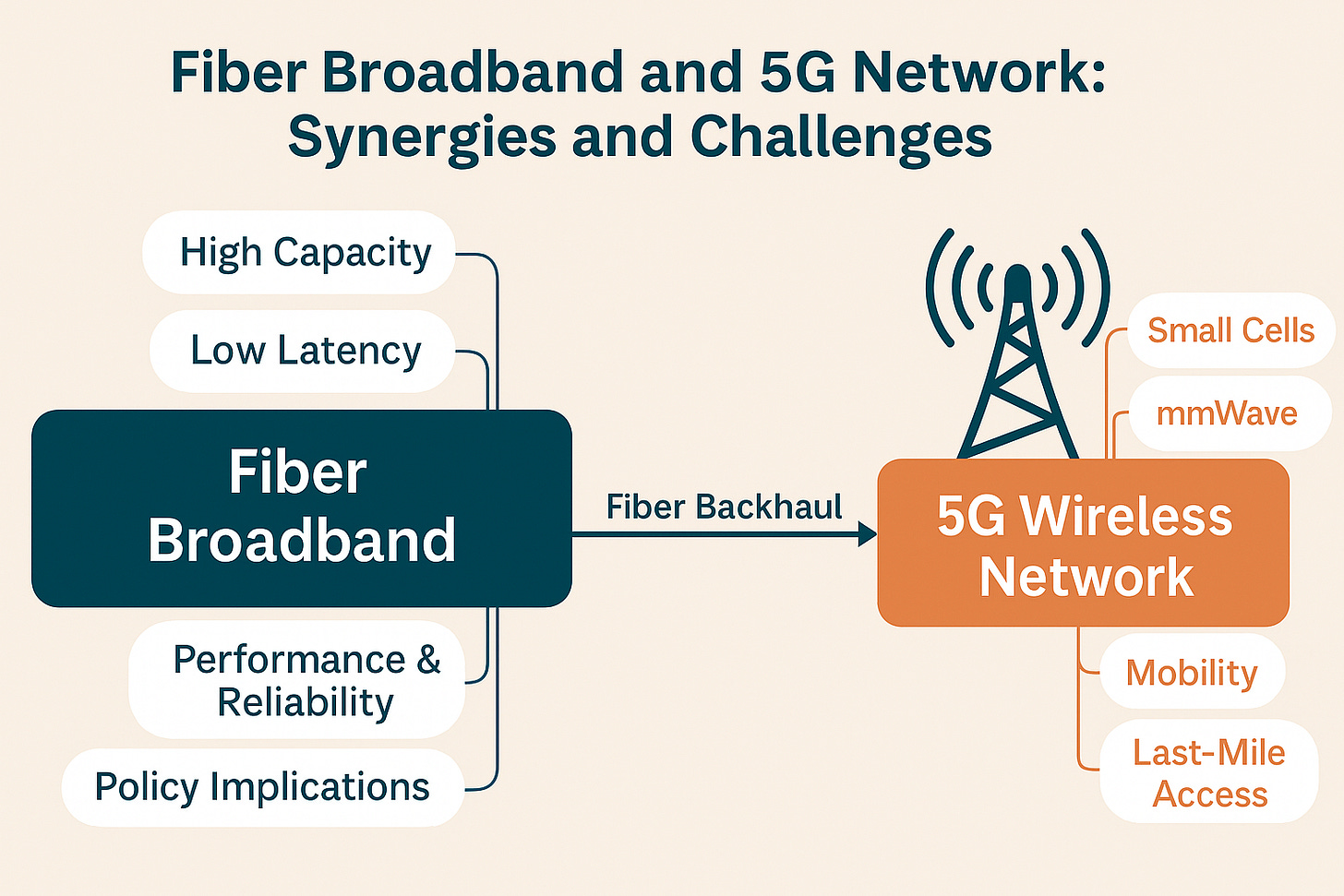

New Zealand has an extensive fibre optic broadband network (coverage is at 87% while uptake lags) and broadband satellite supports remote connectivity.

This was not considered in the policy documents. Fibre optic networks do not present the same safety risks as Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields (RF-EMF) and are relatively politically uncontroversial. A significant weight of evidence, including mechanistic data strongly suggests that low dose Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields (RF-EMF) at levels currently considered safe, and lower, can harm vertebrate systems. An increasing battery of evidence strongly suggests that prenatal and postnatal exposures, and exposures in childhood and youth carry additional risks that are insufficiently assessed in New Zealand. In addition, increasing literature highlights increasing hypersensitivity to RF-EMF.[2]

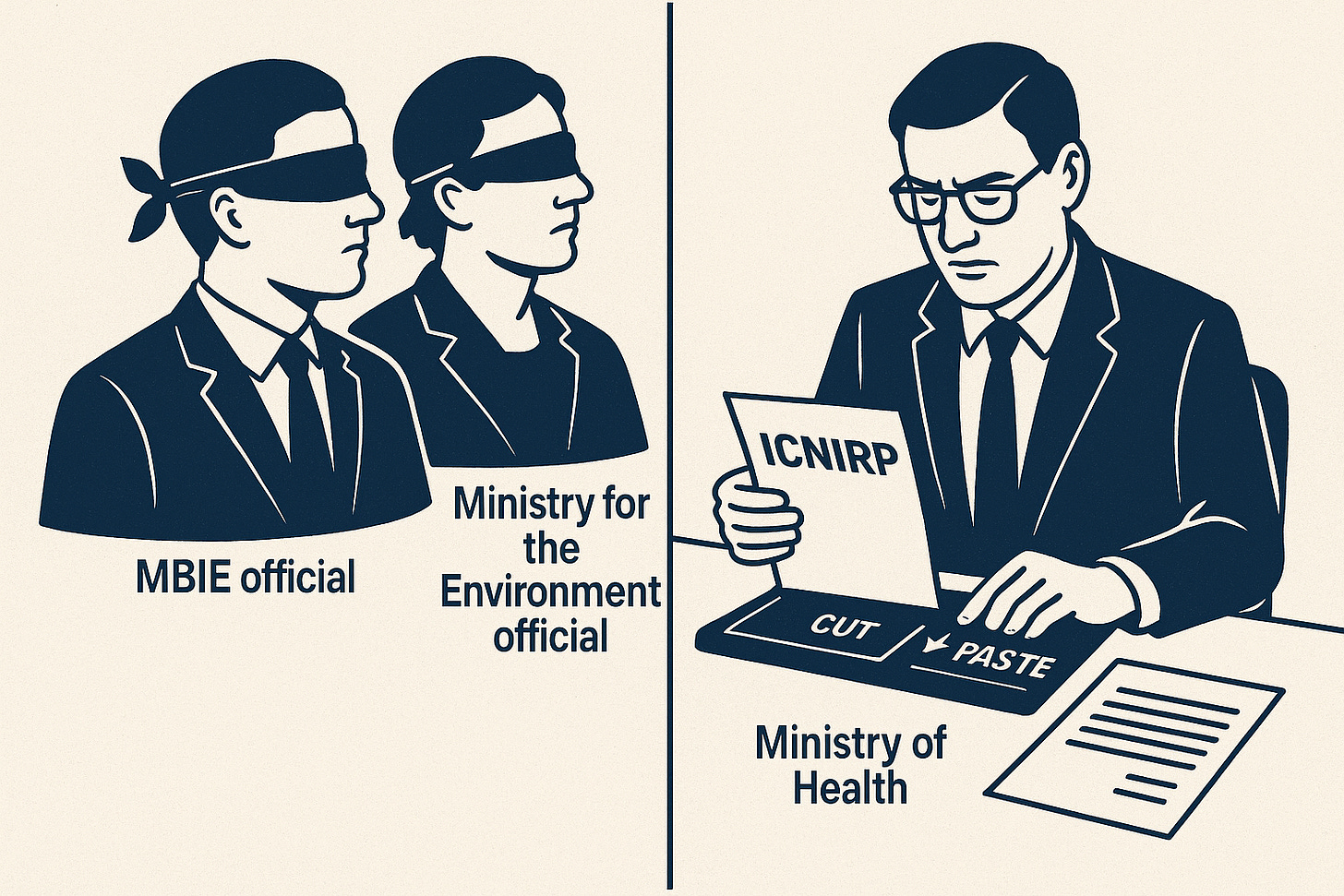

PSGR recommends that special attention is given to poor scientific process by the Ministry of Health, who fail to review the scientific literature on non-thermal effects from RF-EMF and instead harmonise with an institution that itself, does not follow independent scientific process to establish guidelines.

The Ministry of Health in 2018, 2019 and 2022 released unauthored reports which were timed to reflect reports published by ICNIRP in 2018 and 2021, an organisation that self-references and releases publications which are held up as ‘best practice’ but is tightly associated with industry associations. Their policy papers fail to acknowledge the increasing weight of evidence that shows that RF-EMF do not merely harm by heating effects, but that harm occurs non-thermally.

Monitoring studies remain undone, and the MoH does not consider risk from chronic exposures. The increasing concentration (or density) of radiofrequency electromagnetic fields radiation (RF-EMF) that occurs through cell towers, small cell towers, cell phones, and wireless technologies results in chronic lifetime exposures from conception, until death. Therefore, simple dose response studies will not elucidate the complexity of risks that arise in a pregnant mother, a baby, infant, child, adolescent – all the way through to risk in aged care from persistent RF-EMF radiation.

As such any deregulatory actions by MftE and the responsible agency MBIE will be poorly timed, due to the advancing literature which suggests that current claimed safe levels cannot protect health. The mechanisms of harm, including at low-levels, currently claimed safe, were recently beautifully described by Dimitris Panagopoulos and colleagues and which PSGR discuss in a forthcoming release.

As PSGR has discussed, current policies restrict the freedom for scientists to undertake this sort of basic research and so it is not undertaken.

The MftE and MBIE claim that the deregulated telecommunications facilities would be ‘low impact’. It may be presumed that panel antennas, dish antennas and small cell units are low impact, however no definition has been provided.

PSGR recognise that this policy proposal, may be hastily convened to secure weaker standards in advance of increasing acceptance of health risk from non-thermal effects. MBIE’s industry colleagues, may recognise that Ministry of Health claims concerning the alleged safety of non-thermal exposures, supporting the lock-in of relatively high exposure levels, are scientifically indefensible.

The economic impact of digital fibre/satellite infrastructure – not more antennas!

Fibre technology continuously evolves, giving us faster speeds, lower latencies, improved resiliency, greater security, and more flexible applications. Speed records are consistently being broken.[3]

The New Zealand Government initiated the Ultra-Fast Broadband (UFB) initiative in 2009 with the rollout commencing in 2010. Fibre networks are safer than telecommunications facilities (including towers, antennas and small cells on power poles) and politically uncontroversial. Currently 87% of New Zealanders have access to fibre broadband and New Zealand ranks 9th in terms of fixed broadband connectivity.

Ministry officials argument for deregulation focused exclusively on reduced regulatory costs for the telecommunications industry and did not consider safety. There is no requirement for greater densification of towers and antennas in New Zealand urban environments which have in the majority, fibre-optic cabling. Connectivity from handheld devices is demonstrated to be associated with cancer risk and household access to fibre broadband is high. Devices can be more safely enabled through wifi, and devices can remain on airplane mode. The long-term operational performance and reduced maintenance may make fibre optic cabling more economically feasible over the longer term.[4]

The issue that the government needs to address is uptake of broadband connectivity for lower income groups.

‘Nearly a quarter of Pacific peoples are without the internet in the home – three times the rate for New Zealand Europeans and almost twice the rate for Māori. Māori and Pacific peoples are particularly over-represented among younger people without internet access.’

Remote and rural businesses and residences are extensively served by satellite-enabled telecommunications. Starlink supplies broadband to New Zealanders via OneNZ. Starlink is the largest constellation supplying data to New Zealand and, of the 38 systems providing data in the future, it is expected to remain so. Direct-to-satellite mobile services and satellite systems form part of the network architecture, enhance early warning and emergency communications.

More antennas and towers will not add to wellbeing and quality of life for most Kiwis.

PROPOSING POLICIES ARE NOT FIT FOR PURPOSE:

Risk to New Zealand people, is central to this discussion. The proposal substantially expands categories without any focus on emissions risk yet explicitly drafts out any discussion of risk despite the deregulatory context of the proposal – that low-impact telecommunication facilities do not require regulation. The designation ‘low-impact’ is not technically defined in relation to RF-EMF emission strength, leaving unaddressed the potential for approved infrastructure to operate at higher transmission power within permitted thresholds.

The claim that the telecommunication facilities are ‘low impact’ has not been accompanied by any scientifically rigorous analysis. Low-impact is not defined in the 2016 regulations, the 2016 Users Guide, the 2025 Interim Regulatory Impact Statement nor the proposed policy. [5] [6] The Interim RIS did not provide a technical definition as to what a ‘low impact’ would constitute whether an emitting device or a region. As such, there is no disclosure as to the technology spectrum emitted by the claimed ‘low impact’ and any risks in urban environments and to vulnerable communities.

The Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) demonstrates that the health of New Zealanders is not at the forefront of the current policy initiative. Health relating to exposures is explicitly drafted out of scope:[7] There is no evidence for benefits and well-being from this policy proposal, indeed the greater evidence in the literature suggests risk.

Policy problem: The changes to NES-TF is to enable ‘greater efficiency in the deployment of telecommunications infrastructure’. The policy problem is concerned with ‘low impact telecommunication facilities (e.g. antennas, cabinets, poles, telecommunication lines)’ where ‘current rules in NES-TF are too restrictive and do not cover certain low impact telecommunication facilities. This is resulting in the inefficient deployment of telecommunications infrastructure.’ Where a new facility is not currently permitted, telecommunication providers must obtain resource consents which ‘uncertainty, complexity, significant costs and delays for deploying telecommunications infrastructure and services’.

Policy objective: To ‘support efficient deployment of low impact telecommunication facilities that meet the needs of New Zealand households and businesses’ and limit the capacity for territorial and local authorities to set their own standards. The approach consolidates agency power away from local governments. The policy mandate from Cabinet in June 2024 was to make changes to NES-TF [CAB-24-MIN 0246 refers], and so non-regulatory options (such as guidance for councils, voluntary standards, or global consents) were not considered.

Guidance for councils, voluntary standards or global consents) were not considered. Officials also consider that non-regulatory options would be inadequate in addressing the problem definition.

Established protections relating to environmentally significant places and areas.

[47] Changes to radio frequency exposure standards are out of scope. Under NES-TF, telecommunications providers need to comply with the New Zealand radio frequency exposure standard NZS 2772.1:1999 by reference, which is administered and reviewed by the Ministry of Health and Health New Zealand (Te Whatu Ora). The protections for radio frequency exposures will be maintained with no changes. The Ministry of Health and Health New Zealand advised that the references to NZS 2772.1:1999 align with international best practice and remain fit for purpose.

The policy problem and objective has excluded any obligation to ensure the health and safety and hence protection of local communities. This has been enabled through fragmented and outdated policy and legislation which enables the Ministers for the Environment and for Media and Communication to prima facie absolve themselves from any risks that arise as a consequence of such a policy change.

The MftE and MBIE have not made a genuine effort to identify, understand, and estimate the various categories of cost and benefit associated with the options for change.

Reports and data are not held by the Ministry of Health, MBIE, or the MftE to that signal ongoing monitoring, evaluation and reporting that would demonstrate that the agencies have the health of New Zealanders front and centre of this proposal. There is no route for reporting by hypersensitive groups, or groups and individuals that report shifts in health and wellness after a telecommunication facility is installed. Reporting of cases, and documenting them, produces a bank of policy-relevant information. Yet by failing to do this, authorities create a barrier to evidence. Global case studies are identifying changes in health status, and there should not be barriers to reporting this in New Zealand.[8] [9] [10]

There has been no systematic impact and risk analysis. No review of best-practice and the actions of countries that have more tightly regulated equipment, with awareness that the advancing science continues to fail to demonstrate absence of risk and increase knowledge of vulnerability, particularly in key developmental periods. The policy and subsequent proposals do not conform to any standard of safety and risk and are not evidence informed. Neither the RIS nor the Package 1, Part 2.5 NESTF proposal does not conform to good regulatory practice, which is required by The Treasury.[11]

The supporting policy documents fail to review the safety of the status quo, against international best practice and compare this to the claimed safety of the proposed measures in the Consultation. The main argument appears to be to promote ‘efficiency’ because ‘the current rules in NES-TF are too restrictive and do not cover certain low impact telecommunication facilities’. Benefits are structured around reducing consenting costs, claiming that it would reduce downward pressure on prices for consumers, and reduced administrative costs for councils. The benefits are exclusively structure around efficient and timely deployment. No financial assessment was provided. The RIS stated: [12]

Based on the information held, officials consider that the benefits of the proposed changes to NES-TF outweigh the costs.

Responsibility to monitor and reassess the safety of the current allowable electromagnetic exposure limits appears to be drafted out of any white paper or regulatory legislation that has been produced, at minimum in the last decade. Safety was referred to in the RIS – but there was no discussion of the costs of monitoring to ensure that there was standards compliance, and the cumulative level of radiation emissions would not exceed limits.

The action of MBIE and MftE to deregulate reflects a global pattern, where governments act to centralise regulatory power and oversight over the deployment and location of telecommunications facilities, and constrain regulatory discretion. These streamlining clauses remove local government autonomy over these decisions.[13] [14]

However, globally, regions are contesting this increasing regulatory oversight, with increasing numbers of local resolutions being passed (e.g. Hawaii) and with countries independently acting to lower radio radiofrequency exposure limits. These ordinances are feasible because of fibre optic broadband. [15] [16]

Ministry of Health science inadequate for the purpose of policy development:

Public trust in the safety of telecommunications NESTF regulations based on Ministry of Health claims of the alleged safety of non-thermal exposures, cannot be sustained. The regulations are predicated on current standards (NESTF Regs 2016, Subpart 7) being safe.

The standards are upheld by claims of the ‘evidence’ for safety, which arises from unauthored ‘Reports to Ministers’ that are expected to be scientifically authoritative but lack any comprehensive methodology that heavily references a non-government institution which itself fails to demonstrate scientific rigor.

Public trust cannot be expected to be sustained when the government

Explicitly excludes discussion of major concerns about health risk.

Does not transparently publish and update monitoring data.

Does not evaluate such data against published data on risk (including in vitro, case control and cohort studies).

Does not compare NZS 2772.1 with maximum-allowable standards elsewhere, particularly in Russia and Europe.

The NZS 2772.1:1999 is now 26 years out of date. This New Zealand Standard remains in force comprehensively relitigated -- and not by members of ICNIRP, which is closely associated with the telecommunications industry. In the current consultation public concerns as to the safety of the measures would be dismissed as outside the scope of the current proposal.

The New Zealand Ministry of Health has tended to downplay and dismiss cancer risk, while European reviews tend to take risks more seriously. A 2021 European review recognised the seriousness of the cancer risk, finding that radiofrequency radiation is harmful for health[17], while a Committee reviewing 5G deployment stated that:[18]

The 5G radio emission fields are quite different to those of previous generations because of their complex beamformed transmissions in both directions – from base station to handset and for the return. Although fields are highly focused by beams, they vary rapidly with time and movement and so are unpredictable, as the signal levels and patterns interact as a closed loop system. This has yet to be mapped reliably for real situations, outside the laboratory.

Increasingly, standards in European countries more closely reflect these risks.

5G carrier waves create added complexity and health risks that increase risk-based uncertainties:

Use a much broader part of the microwave spectrum including waves with wavelengths in the millimetre range (hence called ‘millimetre waves’).

Extremely complex modulation patterns involving numerous frequencies form novel exposures.

Beam formation[19] characteristics can produce hotspots of high unknown intensities.

Increased numbers of antenna arrays and small cell antennas (which are erected at 200-500m distances along streets) increase exposures.[20]

WHO SETS THE RULES? LIKELY PUBLIC CONFUSION

The 2016 regulations are made under the Resource Management Act 1991 (the RMA) and replace the Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Telecommunication Facilities) Regulations 2008. While the Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Telecommunication Facilities) Regulations 2008 were previously administered by the MftE, the Order in Council NESTF Regs 2016 transferred powers of administration to the Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment (MBIE).

MBIE’s Minister for Media and Communications, (not the Minister for the Environment) sets the policy direction for the communications regulatory system and related infrastructure investments. Funding for MBIE’s components of this portfolio is provided from the Vote Business, Science and Innovation appropriations. As such, there is capacity to provide for monitoring and scientific research to ensure that wireless communications networks are safely stewarded to protect human and environmental health. This is not currently happening.

The Ministry of Health has an outsized role which is unrecognised in the current policy document.

Legal status is established for the standards in Subpart 7 – Radiofrequency fields. Section 55(6) [21]:

§ AS/NZS 2772.2 means AS/NZS 2772.2:2016 Radiofrequency fields – Part 2: Principles and methods of measurement and computation – 3 kHz to 300 GHz

§ NZS 2772.1 means NZS 2772.1:1999 Radiofrequency fields – Maximum exposure levels – 3 kHz to 300 GHz.

The standards in section 55(6) were developed under Ministry of Health recommendations which became legally binding once incorporated into the RMA regulations.

The regulatory framework delegates assessments of risk and safety—including those underlying the proposed 2025 deregulatory measures—to the Ministry of Health. The scientific basis for the safety of the guidelines in section 55(6) rests on the conclusions of an anonymous and unattributed technical advisory body: the Interagency Committee on the Health Effects of Non-ionising Fields (the Committee).[22]

Historically, MftE and MoH had published National Guidelines on Managing the Health Effects of Radiofrequency Transmissions (2000). [23]

‘A key function of the Committee is to review recent research findings, especially recent research reviews published by national and international health and scientific bodies, to determine whether it should recommend any changes to current policies.’ [24]

As such, the Ministry of Health is ‘ground zero’ for administering and reviewing New Zealand radio frequency exposure standards which then enable MBIE, who control the regulations, to deregulate and weaken standards, due to a claimed safety.

As PSGR reference above, any criticism about the safety of current guideline levels has been explicitly drafted out of scope[25] and the policy document advise that Ministry of Health and Health New Zealand advise that:

NZS 2772.1:1999 align with international best practice and remain fit for purpose.

NO ESTABLISHED THRESHOLD WHEN HARM STARTS IN BABIES, CHILDREN & ADULTS

The current safety threshold for adverse RF-EMF effects remains unknown and risk arises from the dynamic interplay between telecommunications infrastructure and whatever device is currently in use. The weight of evidence for risk from RF-EMF emissions presents a complex policy challenge that cannot be delegated to personal responsibility or left to industry self-regulation.

The scientific literature currently does not support further deregulation of telecommunications infrastructure that emits RF-EMF radiation. Evidence supports increasing caution based on the ALARA principle, as low as reasonably achievable, which can be enabled though maximising optic fibre broadband. There is currently no evidence for safety to vulnerable populations: pregnant mothers, infants, children, adolescents and sensitive populations – and harm in early years can translate to years lived with disease, and lower quality of life.

RF-EMF exposures impose an unavoidable burden on vulnerable individuals, denying them the basic right to protect their health in shared environments — an invisible breach of bodily autonomy. A society that saturates its environment with involuntary RF-EMF exposures, knowing some are harmed, cannot claim to uphold the principles of precaution, justice, or public health.

New Zealand policies can proactively care while increasing access to broadband. This includes monitoring and reporting by government agencies, emphasising risk when devices are not on airplane mode, and encouraging downloads before leaving home. Streaming while moving through environments increases risk to health, and telecommunications devices can be kept a strict distance from places where people work, play and sleep to minimise the probability of biological effects, particularly to babies and children. Other, technically practical solutions can reduce the exposures to people from mobile phones, and optical fibre solutions can be emphasised and supported in policy.[26]

The New Zealand NZS 2772.1:1999 standard aligns with the weakest global standards. It provides for a 61 V/m limit (equivalent to 10 W/m² power density at 2–300 GHz) is a generic limit applied uniformly across all environments — schools, homes, public spaces. There are no stricter limits for sensitive environments (e.g. childcare centres and hospitals). No differentiation is made for vulnerable populations. New Zealand does not consider that non-thermal exposures and hypersensitivity are scientifically legitimate risk-based parameters.

The minimal level of RF-EMF that has produced a biologic effect is around 1.7 V/m. A body of evidence supports reducing current limits to a peak value of 6 V/m – as a minimal level that may reduce health risks.[27]

Other countries have stricter standards which demand that cumulative emissions do not exceed the standard:[28] [29]

Switzerland (ORNI Regulation): applies ‘installation limits’ with a limit of 4–6 V/m in locations with prolonged exposure (homes, schools, hospitals). Swiss standards are cumulative for all stations affecting a site.

Italy (Framework Law 36/2001): sets a 6 V/m limit for all living environments (indoor and outdoor). This applies across the full 100 kHz–300 GHz band. Italy’s rule targets ‘sensitive areas’ and cumulative exposure, with no allowance for exceedance even short-term. Local authority measures do exist.

Belgium (Brussels/Wallonia): A zoned approach where regional governments apply varying limits: 3–6 V/m typically near schools, hospitals, and residential zones. The strictest are in Brussels (3 V/m for combined emissions). Municipalities often display antenna maps, requiring pre-installation public notice, and in some cases enforce setback policies.[30]

Russia (SanPiN standards): Takes into account non-thermal effects. 10 µW/cm² ≈ ~6.1 V/m. Cell towers and antennas explicitly prohibited on school grounds and children’s facilities.[31]

Neither society nor governments can expect exposures to have a benign effect on body systems. Insurance companies have recognised the inherent risks and draft in electromagnetic field exclusions in insurance policies, including for non-ionizing radiation exposures. Insurance companies recognise the long-tail nature of these risks – characterised by a long-latency and uncertainty.

A huge body of scientific evidence tells us that exposures are not benign, but harmful. Vertebrate bodies have not altered (or calibrated) in the past hundred years, to account for the increased orders of magnitude levels, of densification of non-native EMF-RF emissions in the surrounding environment.

The Ministry of Health and ICNIRP do not methodically account for the complexities of densified RF-EMF environments, including highly localized intensity peaks, pulsed emissions, and the cumulative contribution of background radiation from multiple personal and infrastructure-based sources. No formal public assessment addresses the chronic, low-level, multisource exposure or the health relevance of peak intensities and modulation patterns.

The concentration of RF-EMF in certain areas — forming zones of constructive field overlap and spatial heterogeneity — remains unassessed. PSGR remains deeply concerned about the biological plausibility of harm from time-varying exposures: asynchronous signals from technologies such as 4G, 5G, and Wi-Fi generate pulsing and modulation patterns that may have effects even where average power densities remain within current guidelines. There is growing evidence linking such exposures to oxidative stress, altered calcium ion signalling, and disruptions to melatonin regulation.

Scientists faced barriers to research exploring and reporting the biological effects of RF power densities less than 10 mW/cm2. In New Zealand, science on RF-EMF is unlikely due to the current policies that are in place by the Ministry of Business, Employment and Innovation. Current science policies reflect MBIE’s innovation focus, and stewardship, basic research and monitoring is not a priority of MBIE.[32]

Historically, agencies tasked with caring for environment and human health would hold powers of stewardship of man-made technologies. However, in New Zealand, business-facing MBIE, as we have discussed, secured control of telecommunications RF-EMF National Environmental Standards for Telecommunication Facilities regulations. Unauthored reports by a secretive Ministry of Health (MoH) committee then provide the justification for retaining 1999 standards in MBIE’s regulations.

PSGR do not believe that MBIE is the appropriate body to steward these regulations. PSGR do not consider that MoH papers form any approximation of scientifically rigorous review.

PSGR consider that the New Zealand population is poorly served by the current governance framework.

The tens of thousands of published papers on the health effects of non-native EMF-RF produce a weight of evidence or a burden of proof. The weight of evidence on risk does not require to be ‘balanced out’ by the evidence of safety, like a game of noughts and crosses. Ethics-based judgement by officials and scientists requires them to categorically protect health. Research demonstrating harm has frequently been undertaken by independent institutions who are not aligned with industry groups or engaged in research on radiation development for medical, military or other purposes.

There are different scientific approaches to understanding whether a technology is harmful. A policy-relevant, science-based approach involves, firstly, an appreciation of daily to lifetime exposures: the breadth (from different devices), duration (from seconds to all day) and extent (from lowest levels to pingback beams between towers and devices).

Secondly, a policy-relevant, science-based approach requires a methods-based evaluation of the existing scientific literature of risk and harm, from mechanistic data to case studies. It involves scrutinising pathways of potential risk to vulnerable populations – pregnant women, infants, children and adolescents, and hypersensitive populations.

A policy-relevant approach involves recognising that there is no known threshold where harm starts. This does not mean there is no evidence of risk or harm – but no evidence for safety.

Harm from environmentally relevant non-native RMF-RF exposures to a developing infant, like the particles emitted from a combustion engine, or the formulation of a chemical in a workplace, cannot be discretely parsed. As with any acute or chronic environmental exposure that disrupts homeostasis, latency, the delay between exposure and disease can occur over years and decades and is inconsistent across people. Hence, an appreciation of the weight, or strength of the evidence is central to any discussion if it is to ethically involve the protection of human and environmental health.

Safeguarding human and environmental health is a fundamental duty of government. Yet under current RF-EMF governance frameworks and regulatory settings in New Zealand, this duty is not, and cannot be, fulfilled.

PSGR’S REPSONSE TO CONSULTATION

As discussed above, the failure to extend cost-benefit to discuss safety was never included in the Interim Regulatory Impact Statement proposing the deregulation of the NESTF Regs 2016 was finalised April 16, 2025, or the Package 1 Discussion Document was released in May 2025 with a corresponding Attachment 1.5.

Unfortunately the consultation questions are framed in such a way that the public will be unable to provide a yes or no answer to address broader concerns.

PSGR will be answering [LINK]:

Do the proposed provisions sufficiently enable the roll-out of upgrade of telecommunications to meet the connectivity needs of New Zealanders?

No -

Neither the Interim Regulatory Impact Statement proposing the deregulation of the NESTF Regs 2016 nor the Package 1 Discussion Document was released in May 2025 with a corresponding Attachment 1.5 reviewed evidence that broadband connectivity needs are addressed by fibre and satellite.

Which option for proposed amendments to permitted activity standards for telecommunications facilities do you support:

Maximum Pole Heights: I don’t support either option.

Limits on headframes on poles in the road reserve: I don’t support either option.

Antennas on buildings: I don’t support either option.

Do you support the proposed amendments to the activity standards:

For customer connection lines to heritage buildings non-compliance with the proposed standard:

Cabinets in the road reserve: No

Antennas: No

Proposed standard should be: Yes - restricted discretionary activity.

No documented evidence was supplied to suggest that this amendment was in any way initiated by, or supported by groups and communities working in or caring for heritage buildings.

Do the proposed provisions appropriately manage any adverse effects (such as environmental, visual or cultural effects)?

No.

Do the proposed provisions place adequate limits on the size of telecommunications facilities in different zones?

No.

Should a more permissive approach be taken to enabling telecommunications facilities to be inside rather than outside the road reserve?

No.

PSGRNZ is a NZ-based charitable trust. We welcome new members - JOIN PSGRNZ

REFERENCES

[1] Order in Council. Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Telecommunication Facilities) Regulations 2016. 2016/281. https://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/2016/0281/30.0/whole.html#DLM6985849

[2] Increasingly referred to as microwave syndrome.

[3] Belden (2024) Looking at the future of Fiber Broadband in 2024. https://www.ppc-online.com/blog/future-of-fiber-broadband-in-2024

[4] Singh A. Integrating Fiber Broadband and 5G Network: Synergies and Challenges International Journal of Scientific Research in Engineering and Management. 9(2)1-8. DOI:10.55041/IJSREM18134

[5] Ministry for the Environment. (May 2025). Package 1: Infrastructure and development – Discussion document. Part 2.5 National Environmental Standards for Telecommunications Facilities. Page 43-51. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment. ISBN: 978-1-991140-86-9 Publication number: ME 1895 https://environment.govt.nz/assets/publications/RMA/package-1-infrastructure-and-development-discussion-document.pdf

[6] Attachment 1.5 Proposed provisions – Amendments to the Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for

Telecommunication Facilities) Regulations 2016 National direction consultation – Package 1: Infrastructure and development. https://environment.govt.nz/assets/publications/RMA/attachment-1.5-national-environmental-standards-for-telecommunications-facilities.pdf

[7] MftE MBIE (April 16, 2025). Interim Regulatory Impact Statement: Amendments to the Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Telecommunication Facilities) Regulations 2016. Pages 1-2 and 20-22. https://environment.govt.nz/assets/Interim-Regulatory-Impact-Statement-Amendments-to-the-National-Environmental-Standards-for-Telecommunication-Facilities-2016.pdf

[8] Nilsson M, Hardell L (2023) A 49-Year-Old Man Developed Severe Microwave Syndrome after Activation of 5G Base Station 20 Meters from his Apartment. J Community Med Public Health 7: 382. DOI: 10.29011/2577-2228.100382

[9] Hardell L, Nilsson M, Case Report: A 52-Year Healthy Woman Developed Severe Microwave Syndrome Shortly After Installation of a 5G Base Station Close to Her Apartment. Ann Clin Med Case Rep. 2023; V10(16): 1-10

[10] Nilsson M, Hardell L. Development of the Microwave Syndrome in Two Men Shortly after Installation of 5G on the Roof above their Office. Ann Clin Case Rep. 2023; 8: 2378

[11] The Treasury (April 2017). Government expectations for good regulatory practice.

https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2015-09/good-reg-practice.pdf

[12] MftE MBIE (April 16, 2025). Interim Regulatory Impact Statement: Amendments to the Resource Management (National Environmental Standards for Telecommunication Facilities) Regulations 2016. Page 7.

[13] Meese J, Hegarty K, Wilken R, Yang F, Middleton C. (2024). 5G and urban amenity: regulatory trends and local government responses around small cell deployment. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance. 26:6 DOI 10.1108/DPRG-10-2023-0150

[14] Environmental Health Trust. Ordinances to limit and control wireless facilities, small cells, and rights of ways. Accessed July 18, 2025.https://ehtrust.org/usa-city-ordinances-to-limit-and-control-wireless-facilities-small-cells-in-rights-of-ways/

[15] See E.g. Hawaii. Bill 24. Ordinance amending chapter 25 of the Hawaii County Code 1983. https://records.hawaiicounty.gov/weblink/DocView.aspx?dbid=0&id=1108131&cr=1

[16] Hawaiian Telcom. (Jan 10, 2025). Hawai‘i to Become the First Fully Fiber-Enabled State by 2026. https://blog.hawaiiantel.com/connections/hawaii-to-become-the-first-fully-fiber-enabled-state-by-2026

[17] Belpoggi F. Health impact of 5G, study for the panel for the future of science and technology, panel for the future of science and technology. In: European parliamentary research service, scientific foresight unit. Brussels; 2021. Available from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/690012/EPRS_STU(2021)690012_EN.pdf.

[18] Blackman C, Forge S. (2019) 5G deployment: state of play in Europe, USA and Asia, study for the committee on industry, research and energy, policy. Luxembourg: Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament. P.11 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2019/631060/IPOL_IDA(2019)631060_EN.pdf

[19] Albanese, R., Blaschak, J., Medina, R. and Penn, J. Ultrashort electromagnetic signals: Biophysical questions, safety issues and medical opportunities (Report No. AL/OE-JA-1993-0055).Occupational and Environmental Health Directorate, Brooks Air

Force Base, San Antonio, Texas, USA. (1994).

[20] Bandara P, Chandler T, Kelly R et al (2020). 5G Wireless Deployment and Health Risks: Time for a medical discussion in Australia and New Zealand. ACNEM Journal Vol 39 No 1 – July 2020

[21] Resource Management (NES-TF) Regulations 2016. Section 55(6). https://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/2016/0281/30.0/whole.html#DLM6985849

[22] NB. Electromagnetic radiation of lower frequencies and longer wavelengths is referred to as non-ionising radiation.

[23] New Zealand Report on EMF Activities. 9th International Advisory Committee Meeting on EMF June 2004. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/radiation/emf-international-project-country-reports/wpro-region/newzealand0304.pdf

[24] Ministry of Health. 2018. Interagency Committee on the Health Effects of Non-ionising Fields: Report to Ministers 2018. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Page 4.

[25] MftE MBIE (April 16, 2025). Interim Regulatory Impact Statement. Page 20-22.

[26] Héroux, P.; Belyaev, I.; Chamberlin, K.; Dasdag, S.; De Salles, A.A.A.; Rodriguez, C.E.F.; Hardell, L.; Kelley, E.; Kesari, K.K.; Mallery-Blythe, E.; et al. Cell Phone Radiation Exposure Limits and Engineering Solutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5398. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075398

[27] Hinrikus H, Koppel T, Lass J, Roosipuu P & Bachmann M. (2023). Limiting exposure to radiofrequency radiation: the principles and possible criteria for health protection, International Journal of Radiation Biology, DOI: 10.1080/09553002.2023.2159567

[28] National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, RIVM. Stam R. (January 2018) Comparison of international policies on electromagnetic fields (power frequency and radiofrequency fields). https://www.rivm.nl/sites/default/files/2018-11/Comparison%20of%20international%20policies%20on%20electromagnetic%20fields%202018.pdf

[29] Environmental Health Trust. Worldwide Policy 5G. https://ehtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/Color-5G-cell-tower-policy-EHT-10.pdf?

[30] Environmental Health Trust (May 2017). Belgium Policy recommendations on cell phones, wireless radiation and health. https://ehtrust.org/belgium-policy-recommendations-cell-phones-wireless-radiation-health/?

[31] Grigoriev Y.(2018). Russian National Committee on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection and EMF RF standards. New conditions of EMF RF exposure and guarantee of the health to population. https://www.radiationresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/021235_grigoriev.pdf?

[32] PSGR (2025) When powerful agencies hijack democratic systems. Part II: The case of science system reform. Bruning, J.R.. Physicians & Scientists for Global Responsibility New Zealand. April 2025. ISBN 978-1-0670678-1-6

Is there an advocacy group on NZ people can report to? I have become sensitive to the degree I'm selling my house and moving a long way from cell phone towers but its opening up a whole new set of issues in that the power company although I specifically requested the analogue meter was to stay have switched it out for a transmitting smart meter so I have no power and I cant get a landline connected so I'm going Amish hehe

This is very sad, but not surprising to read. I have long advocated for people to switch off all devices every night in order to give your own household AND your neighbours a bit of a break from exposure.. 6-8 hours is better than nothing and everyone who does this saves power and money as well... The research just has not been done and BigTelco knows this and only cares about profits...