When your science, research, innovation & technology system lacks an ethical base and a public purpose.

Science System Advisory Group (SSAG) Phase 2 consultation

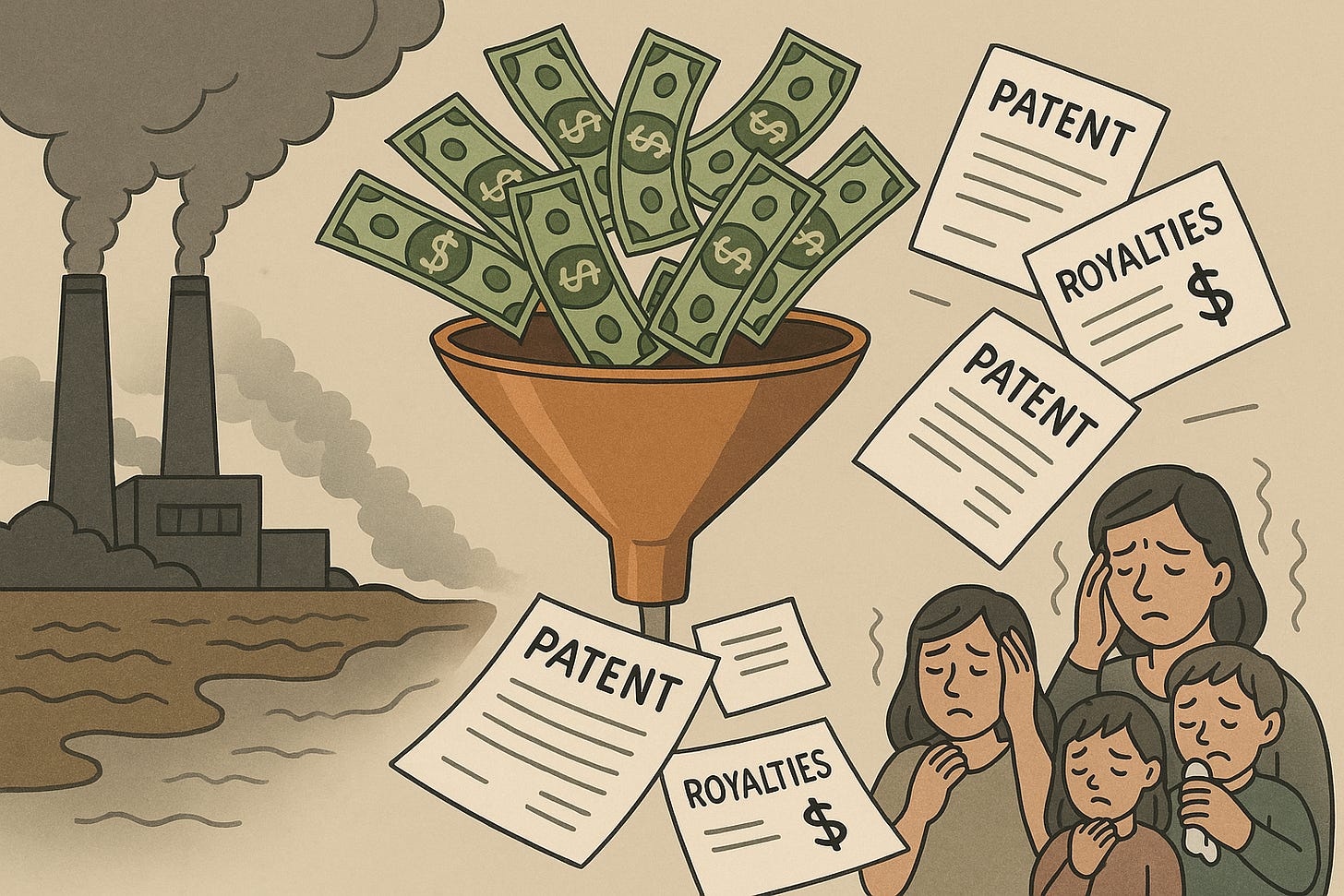

PSGR have just sent in a quickly drafted response to the Science System Advisory Group (SSAG) Phase 2 consultation, due at 5pm today. The SSAG ask specific questions. However, PSGR suspect that a big (and undeclared by the SSAG) problem is that the science, research, innovation & technology system (SRI&T) has been - and is becoming more tightly geared to - just producing innovations - patents, royalties and commercial outcomes. That looks to be the purpose of the current science system reform, which has been controlled by the Ministry of Business, Innovation, Employment and the Hon Judith Collins (and now handballed to new science Minister, Shane Reti).

There is no language in the SSAG to support the public purpose, to problem solve in the context of New Zealand. This can lead to lots of downstream problems, from politicians that adopt short-term solutions, to scientists that won’t address controversial topics because they’re afraid their funding will dry up, to sick people that aren’t being treated as well as they could be, to shoddy infrastructure because there is no research support from the departments that should be doing the work, but no funding for scientists to fill the gap.

Our response is a bit rushed and repetitive, and probably (for some!) badly worded as SRI&T challenges and issues are complex and overlapping, it’s a big topic. We’ve also been prioritising other (related) work, which we aim to soon release, so please bear with us!

Response: Physicians and Scientists for Global Responsibility New Zealand Charitable Trust.

Email: info@psgr.org.nz

Phase 2 Consultation: Phase 2 consists of high-level questions regarding the funding tools and mechanisms for the science, innovation and technology sectors.

Where possible it may be useful to distinguish short-term issues from longer-term desired outcomes.

Questions

In what areas must New Zealand have or develop in-depth research-based expertise over the next two decades?

The capacity for public-good problem solving across interdisciplinary areas has been displaced and replaced by an ‘innovation’ based funding trajectory over thirty years. This has resulted in the enclosure of science and research for commercial purposes, and a restriction of creativity in the service of the nation. In-depth research based expertise must be reframed and instated with an obligation and culture of serving public purpose. Research, science, innovation and technology (RSI&T) institutions must have the power to not only enable in-depth research-based expertise, but have demonstrable capacity to engage in public-good cross-disciplinary partnerships, in service of New Zealand, her people, resources and environment.

Minerals and materials engineering: the underfunding of basic research, including university-based research has led to conservatism in early career researchers, and the capture of trajectories by senior scientists who focus on what will fall under an ‘innovation’ and ‘excellence’ scope and not contradict political beliefs. This has prevented the identification and taking on of national challenges which require interdisciplinary research schools to collegially co-operate and a creative approach to materials development, and engineering.

Infrastructure: Institutions do not have long term funding and research capacity to address issues that require deep knowledge, but which can be hamstrung by short-termism and politics. Two examples. [1] A gap in resourcing for long-term basic research and analysis of best practice public transport infrastructure, this includes materials, energy, costs, logistics and environmental factors. [2] An absence of resourcing for independent long-term reviews of drinking water filtration and wastewater treatment infrastructure to support local council decision-making.

Arable, horticulture and livestock agriculture, forestry, fishery: MBIEs disproportionate focus on innovation, genetics and climate change has led to the underfunding of knowledge regarding to environmental drivers of poor performance, including poor reproduction and productivity, and disease risk (infectious, acute and chronic). For example there are barriers to research for soil health, drought and weed resistance, while funding is over-directed to CO2 emissions. Current funding patterns restrict funding applications if the multidisciplinary approach is too novel, too open-ended and not short-term enough.

Environmental research: Absent: Secure research infrastructure for the conduct long-term research into the environmental and manmade drivers of pollution and toxicity (human health and environment). The CPHR is vastly underfunded and the ESR survives on short term, cherry-picked funding for pre-politically approved endeavours. New Zealand lacks an institution with secure access to long-term funding to research accumulative toxicity, where multiple chemical contaminants may accrue in drinking water or groundwater, and their risk, and then make policy-relevant recommendations. There is no institution with funding to evaluate new data on electromagnetic field risk (for ionic, non-ionic radiation, hypersensitivity and developmental and cancer risk) which can freely evaluate the safety of the current standard NESTF NSZ2772:1 1999 standard which is based on a standard provided by ICNIRP, an organisation that is sponsored by vested corporate interests.

Medicine: There is a pervasive and intolerable ignorance across the medical field of the potential for conjunctive use of medical and nutritional therapeutics in the support of acute and chronic care, including mental illness and infectious disease. There is resistance to adopting new technologies to identify and understand environmentally mediated disease. Long-term research on serum testing or biomarker testing for the detection of disease patterns and disease drivers to support symptom detection and disease reversal is impossible under current funding pathways.

Human health and nutrition: There is no language of optimal health in New Zealand. Health research policies are oriented to providing medical treatments and therapies for the sick and diseased and ensuring optimum takeup. Long-term research to identify optimum nutrition levels, techniques to reverse mental and chronic illness, and securing a greater knowledge of human biological function for the purpose of ‘biohacking’ to reverse complex disease is outside the scope. The biohacking market has an CAGR of 18.9%.

Robotics and electrical for industry (including agricultural) applications. The discussion in the engineering, infrastructure and agricultural sections apply here.

Digital/in silico: It is politically and financially infeasible for researchers in the RSI&T system to undertake long-term research that would look critically at the current aims of the ‘digital government’, the role and power of large global services providers and evaluate whether the current government apparatus of digital government, and the future frameworks proposed in policy, will serve the long-term interests of the people of New Zealand. Long-term public good research to evaluate the extent of private and public surveillance, the potential for abuse of power by public or private interests, the challenges of AI, the use of technology at primary, secondary, and tertiary level are all outside funding scopes. Funding for research groups to develop New Zealand-designed solutions, for example to keep government information and data stored by the public sector, to trouble-shoot and identify social and practical problems with artificial intelligence are all outside the scope of most funding programmes, either because of the innovation requirement or because the only funding programmes are too short-term.

Policy and governance: the production of policy-relevant information, and the relationship of scientific knowledge with principles of ethics, stewardship and the rule of law. This would bring in and integrate knowledge, such as has been described in the sections above, to ensure that decision-making in government was not vulnerable to the political whims of the government of the day, and that policy-related science claims could be assessed, and if necessary, challenged or refuted.

PSGR do not believe that this consultation is sufficiently rigorous and impartial so that it may serve both the needs of the research, science, innovation and technology sector as well as New Zealand, her people, resources and environment. This must be a more extensive and more considered process beyond a one month input to the SSAG committee which was itself followed by another fast-tracked consultation process.

The SSAG committee lack a broad cross-industry background. The SSAG committee are disproportionately weighted with prominent political advocates from particular technology sectors. Committee membership is hence not appropriate for this purpose of consulting on behalf of, nor recommending policy, direction and framework of the future research, science, innovation and technology sector.

Question [1] does not ask qui bono – what is the intended outcome of RSIT funding? New Zealand has had no overarching ethics based value to drive the RSI&T system. This would assist to ensure that the institutions within the RSI&T framework would be able to clearly identify their priorities and accord to public-good or commercial priorities. It would support the setting of budgets to ensure that there were RSI&T research pathways to support problem identification, trouble-shooting and the development of solutions for the benefit of New Zealand, - her people, resources and environment.

Question [1] fails to ask – how do we identify what research needs to be undertaken? Current funding paradigms ignore how we identify much needed research. Currently prioritisation in the main, is centred around a hope of a financial outcome via the lodging of intellectual property, as patents are a proxy for growth.

We attempt to answer these questions in the context of the SSAG’s redefined questions.

In the 30 years since innovation and excellence became the guiding principles for the research, science, innovation and technology (RSI&T) system, New Zealand’s population has increased by 2 million. The innovation focus has shunted the RSI&T sector into a closed loop paradigm, where the laboratory heads spend 20% of their work hours designing funding applications, based on their existing expertise, that will be conservative (a bit ‘fringe’) and not challenge any normative scientific perspective. There cannot be any challenge of established scientific consensus and there cannot be any challenge or explicit or implicit criticism of government policy or of the large industries that work closely with governments and political parties to establish policies.

Current policies have effectively established a conservative policy police, where convention must not be challenged. This produces a downward spiral where innovation can ‘think’ smaller and smaller (often as applied tweaks to known concepts), but not address large problems.

The RSI&T system is entrapped by policy and by the obligations of funding committees to follow policy and align with preset funding parameters, because the ‘areas’ that can be selected must be preordained and politically acceptable. The RSI&T system is effectively politically neutered and unable to serve the public purpose.

At what levels should research prioritisation occur?

Remove the responsibility from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. Stop this current science reform process and restart a public open process that engages more widely. The language in the Phase 1 report demonstrates that the SSAG accept the current economic growth and commercialisation perspective and lack any capacity to address the inappropriate direction of the entire RSI&T system.

The past 3 decades have prevented scientists from actively thinking and collaborating to address large issues. RSI&T system staff are not used to discussing politically controversial issues. Conduct a three-week open science symposium where researchers, scholars and scientists discuss New Zealand’s biggest problems.

What are some criteria for research selection?

The SSAG do not have a terms of reference to evaluate how research selection should be re-evaluated at the highest levels.

Overarching principles which could include public good, the severity of a known problem, the social, physical, economic cost to the people and environment of New Zealand would drive institutional selection and development and funding decisions.

Funding panels in different expert sectors could then differently take into account factors including the severity of the identified problem, relevant knowledge gaps, innovation, excellence and impact. However, public benefit and the juggling of what is important and critical would then be part of the necessary judgement faced by funding panels. Public benefit is the key drivers. Principles would be the primary concern.

In the current RSI&T system, innovation and excellence are the key denominators, then impact, then public good goals. Researchers understand that if they do not do this, they will not be funded. RSIT researchers must calculate to protect and preserve their careers, and they must protect their ‘patch’ because innovation and commercialisation are key features of success.

Is this a worthy topic that addresses a known problem? Our answer above suggests some broad deficits. This cannot be answered for example, because many of the problems are not politically acceptable to be discussed in New Zealand.

Ø For example, a multidisciplinary research proposal to reverse metabolic syndrome would fail because the Ministry of Health does not recognise metabolic syndrome. The same for cancer, because the prevention and reversal of cancer is more tightly related to environmental exposures than genetic status.

Ø Proposals to undertake research to identify back door, and surveillance and governance risks that arise from the New Zealand/Microsoft contract would fail because Microsoft would not approve.

Ø A multidisciplinary research proposal to assess chemical toxins and trace element pollutions in agricultural soil would fail because there is no innovation outcome, even thought it may relate to long-term soil productivity.

Ø A research proposal to consider the drivers of autism and neurodevelopmental delay would be rejected because it would involve to many different areas of expertise, traversing molecular biology, toxicology, neuroendocrine, data analysis and so on.

What is the value of research roadmaps in priority areas?

Research roadmaps promote transparency and help outsiders understand the extent to which the research is worthy and relevant.

But research roadmaps must occur in a larger framework of serving the public purpose.

Does New Zealand need to rationalise its funding mechanisms?

New Zealand needs to re-evaluate the purpose of the RSI&T system and rationalise funding mechanisms to ensure that public resourcing fulfils the public purpose.

For three decades mission-oriented RSI&T has only occurred within a politically acceptable framework that harmonises with innovation mindsets, or cultures. RSI&T operators have been hamstrung as many large interdisciplinary problems which require a mission-led approach would also challenge scientific paradigms and the political status-quo of successive governments and agencies.

This cannot be undertaken through the SSAG committee who have failed to articulate many of the problems outlined in the Te Ara Paerangi consultation, particularly the way competitive funding has been managed which has encouraged fragmentation, distrust while reducing the collegiality necessary for addressing large problems.

Should we have multiple funding agencies or combine them into a single entity?

A short term SSAG consultation is not sufficient to address this problem. PSGR do not think the SSAG process can produce a suitable outcome that will be robust, fit for purpose, and serve the public interest. With that in mind:

Universities should shift back to their core purpose of knowledge and education and not have commercialisation arms.

CRIs/PROs must revert to transparently and publicly addressing big issues for the industry sectors that they serve. CRIs/PROs must not be ordered to maximise innovation, but to serve the public interest with particular focus on problem solving services for small and medium sized New Zealand businesses, and New Zealand farmers and growers. CRIs/PROs must own all IP, and this must not be owned by the scientists, but be considered a public asset. Perhaps 3 institutions could be set aside for explicitly commercial purposes, but which could integrate skills training (see below).

Private public partnerships in the RSI&T system with foreign corporations must not exist. There must be no secret contractual arrangements with corporations.

There must be priority around developing New Zealand owned businesses and problem solving to enhance New Zealand owned industry.

What kind of funding instruments should be used and in what circumstances?

Block funding: Interdisciplinary research for long-term problems which is led by cohorts with varied levels of expertise.

Short term funding: new grants, small projects.

Remove commercial and innovation imperatives from all but 3 institutions which are explicitly designed to commercialise inventions with loan facilities at the proof of concept stage. There are to be no secret agreements with corporate partners. These 3 institutions must interface with universities/polytechs and CRIs/PROs. The profits from these 3 institutions must be publicly declared and return from the public. The development stage can be funded by investors, but these investors must be New Zealand citizens, reside in New Zealand and/or be small to medium size companies. Large monopoly-like institutions require competition for market economies to work, and policies that promote competition in smaller market players can help prevent abuse of power by large monopolistic/cartel-like industries.

The commercial institutions would be in place to for skills development and training in challenging interdisciplinary environments, e.g. Infrastructure and geotechnical engineering; digital software, data analysis for human health and reversal of chronic illness; agriculture, electrical and robotics; artificial intelligence, algorithmic manipulation and data mining to maximise human flourishing and prevent abuse of power.

How would a funding agency balance these different expectations?

The absence of a language around ethics and need means that all decisions are so-called, technical. Once larger big problems are no longer censored, but may be addressed, it can become clearer to identify problems.

Funding panels of working scientists, who are tasked to base funding on solving challenges and problems in New Zealand, not allocating funding based on the likelihood of a commercial outcome, change the freedom which those panels can balance the public purpose.

The block funding mechanism will allow research over time is managed by the participating scientists. There should be slack built into the funding to allow for unexpected costs or discoveries to take place.

For example: robotics in forestry to identify and eliminate weeds and wilding pines, and prevent toxic water run-off, would involve cooperation between materials engineers, physicists, software engineers and forestry industries, and this funding could result in widespread benefit across the industry.

A similar funding pot to develop one strain of genetically engineered pine tree, which would be controversial, which could involve in wilding, or in cross-species contamination and utilise a narrow range of biotechnology skills, might not be as worthy and not carry the same cross-industry margin of benefit.

How should high- intellectual risk but potentially high-reward research applications be identified and funded?

The question is what is ‘high-intellectual risk’ and ‘high-reward research?’ Is it for public purpose, is it permitted to challenge status quo norms? Government policy?

When RSI&T cohorts are not supressed into only researching what is politically acceptable, they can have more freedom to work out what is the most important issue.

Currently the only way this question can be answered is by picking the most elite scientist with the most proven track record. This does not allow for important work that will solve public problems and challenges.

The past three decades has shown that large funding pots of over $500k will only go to research that is tied to an innovation outcome. All scientists know that their funding proposal must be innovative and promise some sort of IP as an outcome, and they know to be ‘excellent’ that their research must accord with convention in their discipline. As to impact, this is the ‘hope’ factor and in medical terms is often associated with the temporary suppression of a disease.

Because of the lack of principles and high-level obligations to support research for the public good, in the current and proposed RSI&T system, large funding pots for multi-year research over $5 million will never become available for groups that would proposal a critical investigation of the following issues: non-chemical integrated pest management for forestry, agriculture and aquaculture; soil biology; chemical contamination of wastewater; nutrition for infant health; dietary (non-medical) drivers of cancer and/or chronic illness and/or mental illness; the safety of vaccines and medicines; the safety of electromagnetic fields by age and stage; anthropogenic climate change; and the management of livestock and crops for a changing climate to feed the New Zealand people; long term research to understand contract secrecy for public infrastructure development, from water services, to roading; research groups to critically evaluate security and privacy of digital services that are either owned and controlled by governments or contracted by foreign corporations.

Many people may recall the fate of Gravida which was meant to have freedom to research health in infancy and childhood, but became disbanded. Many have watched how the Sustainable Farming Fund has become more closely tied to innovation outcomes, rather than broader purposes which could include supporting soil fertility, livestock health and productivity and protecting surrounding systems, over the long term. We’ve observed how the ESR scientists are kept on a politically manageable tight budget. For example, the scientists re-evaluating drinking water standards had no capacity to critique the out-dated nature of the current World Health Organization standards and guideline levels. There was no effort to understand mixture effects, nor assess whether current drinking water services had capacity to filter out environmentally relevant levels of chemicals that may have contaminated local water sources.

The problem has been compounded by tight managerial focus and oversight, and the ongoing institutional levies imposed when SRI&T research groups achieve funding success. However, the short-term nature of funding and overhead costs ‘mining’ has fostered short termism around laboratory equipment and instrumentation, and the inability to retain skills.

How should research involving the study of or the application of Mātauranga Māori be managed and funded?

We suspect that the rhetorical use of the term is being used as a political proxy substitute which enables policies to undermine or set aside the obligation to uphold the Treaty of Waitangi.

As PSGR understands the current system to work, for example, currently if Māori sourced funding under a Mātauranga Māori theme it would have to be applied within an innovation framework. Anything involving equity must be within an innovation framework. This is the case for health research if there is to be an application for a large funding injection over 500,000.

Large funding pots will not be allocated if there is no ‘innovation’ outcome. For example, a 6 year, $60 million inter-disciplinary project to assess serum levels of basic nutrients, to identify biomarkers for disease, to evaluate risk-based dietary patterns (in New Zealand and in the scientific literature) in the 0-25 year age group, in order to create, collegially across New Zealand a pathway to reverse metabolic syndrome and diabetes in Māori would fall outside the demands of both Mātauranga Māori and innovation funding frameworks.

Work to understand and then reverse chronic and mental illness conditions in Māori at scale would then continue to remain unfunded and undone. Work to find a molecular pathway for a new drug, would be funded.

How should New Zealand address expensive research infrastructure needs such as access to supercomputing, bespoke lab equipment or spaces, and data requirements?

Recognising that Treasury and the appropriations process can equip universities and labs through the process of money creation.

The only way that this is not exploited, is to ensure that lay department managers do not have long term control over the funding mechanism, that funded cohorts must act transparently and collegially in a negotiated process, and that there are no secrecy and commercial in confidence agreements (i.e. private public partnerships) where corporations can exploit use of public assets (including knowledge assets).

By building transparency and trust into the system problems and challenges will still happen, but there is greater likelihood that they will be discussed and rectified.

What does New Zealand do to improve workforce retention and develop the research workforce from the early career to the mature? How does New Zealand ensure the retention of research/innovation leaders?

Three decades of innovation, commercialisation and the necessary commercial in confidence agreements have resulted in a dislocated, protective and inwards-looking RSI&T system that is hampered by short-termism and a focus on finding the next innovation to ensure that the next funding round will be successful.

A cultural shift by serving the public purpose will result in greater collegiality and collaboration across institutions.

The challenge is often ‘dead wood’, however, when the secrecy and commercialisation imperatives are removed, scientists are far more purposeful. collegial, and trusting of each other, and can work with colleagues to prompt them into public good work, or change their ways.

The Treasury and appropriations process should be ensuring that the New Zealand RSI&T is in place to address long term challenges.

Are there other key issues (beyond the quantum of funding) that should be considered in the science and innovation system not yet addressed in this or the previous report and consultation?

For thirty years, uncomfortable or politically inconvenient questions have been systematically deprioritised in funding rounds. Scientists on funding panels know this, and the scientists applying for the funding know this. Self-censorship is common.

Scientists are unwilling to expose their research labs to failure in a funding round. They will apply for ‘safe’ funding. They do not want to risk their status nor their career from a funding rejection. Research questions with difficult endpoints, that are difficult to quantify and with uncertain outcomes will not be asked, particularly if they challenge prominent industry funders to their institution.

This is producing research voids, path dependency where future funding is dedicated to the ‘known problem’ that is politically palatable. Larger and greater problems go unfunded.

What we also see is a decline in courage – RSI&T researchers too timid to posit, speculate or guess, across complex interdisciplinary subject-matter areas, because the single discipline sceptics will challenge their scientific authority.

We see RSI&T institutions reluctant to speak publicly, and their staff condemned if they speak publicly about a ‘political’ issue.

It’s fine to speak about innovation and commercialisation in public, but not about something wrong with an industry sector, a research programme, a non-greenhouse gas emission (such as pesticides or EMF/5G exposures) a drug or digital technology.

NB. If you are a scientist or researcher in the public system, and disagree with our comments, or might add to our knowledge of this topic, PSGRNZ would very much appreciate you reaching out to us to correct us and/or advise us. You can email us at info@PSGR.org.nz, or if you would prefer, send an anonymous letter to: PO Box 16164, Tauranga 3147.

No need to be self-critical! A very thorough and readable submission - any repetition makes the point more prominent. Thanks for the work...