The link between food addiction & poor metabolic & mental health.

The health burden from refined carbohydrate consumption & the close relationship with food addiction can no longer be swept aside.

Cumulative carbohydrate burdens from excess sugars and starches not only impacts the body – they impact the brain. Scientific studies consistently show that by lowering blood glucose and triglyceride levels via reduction of carbohydrate intakes, people lower risk for not only diabetes, cancer and heart disease, but a wide range of psychiatric conditions. This is not addressed in official policy.

The orthodoxy of a discrete medication for each symptom, or a suite of symptoms is being overturned as scientists and doctors demonstrate how excess blood glucose, unstable insulin, and low-nutrient, low-fibre ultraprocessed foods containing inflammatory oils and toxic chemicals drive multiple conditions - multimorbidity.

The increasing prevalence of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus shows us that current policies not working.

More and more people are being diagnosed at younger and younger ages.

This is a public health emergency because insulin alleviates symptoms but doesn’t prevent all the other associative risk factors that drive what is referred to as metabolic syndrome.

The burden of carbohydrate-rich diets has been challenging to address, but increasingly scientists, doctors and patients are finding a language for food addiction.

They’re developing skills to navigate low-carbohydrate, whole-food diets that are not burdensome to the individual and do not spike glucose. Individuals respond differently to dietary carbohydrate intakes and approaches tailed to the individual is a key component of any reform strategy.

By moving away from refined, high carb diets and being much less likely to cascade through a known sequence of diagnoses which involve more and more drugs at earlier and earlier stages - people lower their risk of multimorbidity (the strong likelihood that they will be diagnosed with a spectrum of medical conditions) and can miss out on a lot of misery.

Misery because it's not just fatigue, brain fog, gut dysbiosis and irritable bowel, constipation (or the opposite), going blind early with glaucoma, erectile dysfunction, the side effects of all the different medications that keep coming (because insulin doesn't stop metabolic syndrome, it stops key symptoms of T2D) - better nutrition translates to more energy, better sleep and better mental health. The scientific papers supporting this knowledge are growing at a rapid pace.

Doctors have faced barriers to advising their patients on dietary matters. For example Dr Sandford’s warning from superiors, when she was advising a client to reduce carbohydrate intakes when he was diagnosed with progressively worsening eye conditions. The scientific evidence was robust that T2DM increased risk for poor eye-health outcomes. Yet clinic management warned her against making such recommendations because her training was not specifically in nutrition.

PSGRNZ’s YouTube account has a playlist on nutrition and health.

THE CARB-GLUCOSE-INSULIN ROLLERCOASTER

THE MECHANISMS:

ELEVATED BLOOD GLUCOSE & THE CASCADING HEALTH CRISIS

Complex carbohydrates (starch) include sugars are ultimately broken down in the digestive tract by enzymes into their simplest form, glucose. For example, wheat flour and white rice can contain roughly 70-80% starch. Muscle and other body tissues use glucose as a rapid fuel source, particularly during physical activity, while the liver and muscle cells store excess glucose as glycogen, a compact, easily mobilised energy reserve.

Starches vary in their digestibility: they may be rapidly digestible, slowly digestible, or resistant to digestion, and their characteristics can be significantly altered by domestic cooking methods and industrial processing. As with sugars, excessive consumption of rapidly digestible starches is associated with adverse health outcomes. Understanding differences in starch digestibility, and how quickly blood glucose levels rise after consuming starchy foods, is an important aspect of public health.[1]

High blood glucose (hyperglycaemia) and unstable insulin levels can be toxic to cells and to the mitochondria. Glucose is absorbed into the bloodstream, raising blood sugar levels (known as HbA1c). In response, the pancreas releases insulin, a hormone that signals cells to take up glucose for immediate use or storage.

The body’s glycogen storage capacity is limited. Once these reserves are full, continued high glucose availability, especially from repeated exposure to refined carbohydrates, triggers the liver to convert excess glucose into fatty acids through a process called de novo lipogenesis (DNL). These fatty acids are combined with glycerol to form triglycerides, which are packaged into very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) and released into the bloodstream. These small, dense lipoproteins are more atherogenic. Elevated circulating triglycerides can be transported to adipose tissue for long-term storage as body fat or used by muscle tissue as an alternative energy source when needed. [2] [3] [4] [5]

Insulin, the master regulator of energy metabolism, is central to this process: it not only lowers blood glucose by facilitating its uptake but also promotes fat storage by encouraging triglyceride uptake into fat cells and inhibiting fat breakdown. Over time, consistently high carbohydrate intake, especially from refined, high-glycaemic sources, can lead to chronically elevated (compensatory) insulin (hyperinsulinemia), increased triglyceride levels, and greater fat accumulation.

This is not simply a theory. A burgeoning scientific literature consistently shows that insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia with key conditions that are prevalent in modern society: development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular disease, cellular senescence and cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases. [6] [7] [8]

An increasing range of studies, from mechanistic and biomarker studies to case studies and trials provide firm scientific evidence for carbohydrates as a primary driver of obesity and metabolic disease via this insulin pathway, rather than the historic consensus position that calorific consumption is the primary driver of obesity.

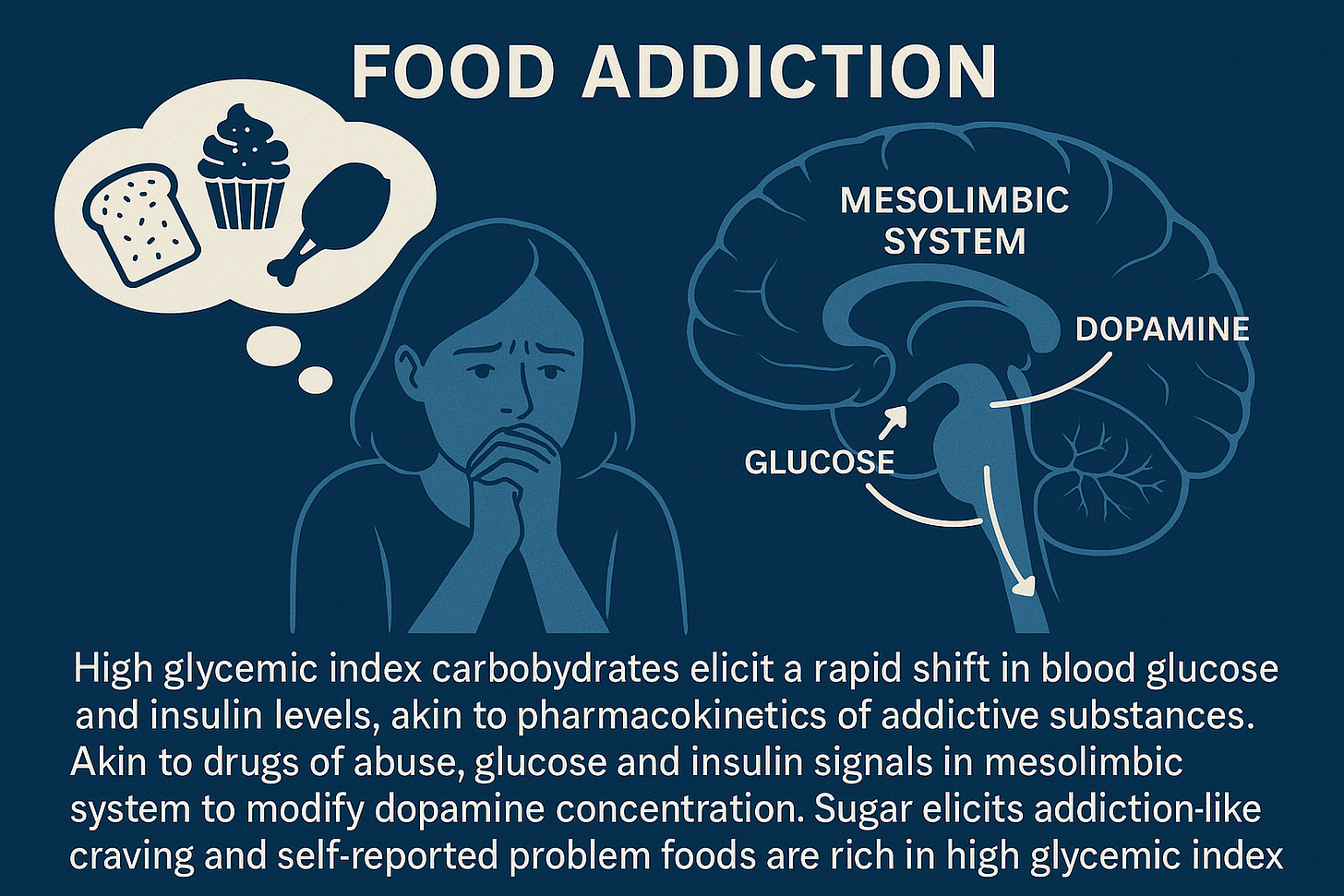

While people do not become addicted to protein or vegetables, a high glycaemic carbohydrate intake (especially if spread over multiple meals/snacks) results in repeated postprandial glucose spikes.

These glucose spikes are associated with dopamine release, and carbohydrate consumption impacts people differently.[9] Researchers are recognising that multifactorial drivers plausibly amplify health risk:

High glycemic index carbohydrates elicit a rapid shift in blood glucose and insulin levels, akin to the pharmacokinetics of addictive substances. Akin to drugs of abuse, glucose and insulin signals in the mesolimbic system to modify dopamine concentration. Sugar elicits addiction-like craving and self-reported problem foods are rich in high glycemic index carbohydrates. These properties make high glycemic index carbohydrates plausible triggers for food addiction. [10]

Cumulative carbohydrate intake encompasses the everyday cereals which include rice, wheat, rye, oats, barley, millet, and maize (corn) but also a new and growing class of food - ultraprocessed food.

When do glucose spikes stop and start?

What is the level where people are ‘unable to resist’ - tolerate cravings?

These are important questions because - to repeat - insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia with key conditions that are prevalent in modern society: development of T2DM, cardiovascular disease, cellular senescence and cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases.

The devastating reality is that for many, mental illness is commonly associated with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia and T2DM.

ULTRAPROCESSED FOODS & FOOD ADDICTION

Emerging lines of evidence indicate that the metabolic and mental illness crisis is amplified by a class of food product, ultraprocessed foods, that are engineered to be hyper-palatable and addictive.

PSGR talk about the risk from technology, and chemical and other exposures.

Ultraprocessed foods are a technology. They are synthesised to encourage repeat purchasing - addictive behaviours.

Ultraprocessed foods are formulations of low-cost ingredients, mostly of exclusive industrial use, that result from a series of industrial processes. These processes involve the fractioning of whole foods into substances which are often derived from a few high-yield crops. Some of the substances can undergo hydrolysis, or hydrogenation, or other chemical modifications. Colours, flavours, emulsifiers and other additives are frequently added to make the final product palatable or hyper-palatable and ensure a long shelf life.[11]

Carlos Monteiro (X profile) first described ultraprocessed food as a component of the NOVA classification system. Professor Ashley Gearhardt has since taken that definition, and developed the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) to enable researchers to assess and understand addictive eating behaviours.

PSGR interviewed Ashley last year:

In the U.K., Dr Jen Unwin has been spearheading Food Addiction Solutions and publishing evidence of the success of food coaching in the scientific literature. A recent Daily Mail article suggests that Unwin achieving traction on this issue in the U.K.

In a 2025 conference presentation Dr Jen Unwin described the cycle the ultraprocessed food addiction trap:

Hyperpalatability.

Suppression of frontal lobe activity.

Neurons that fire together, wire together.

Damage to the mitochondria, leading to energy deficits.

Negative reinforcement: a bad feeling state is temporarily relieved.

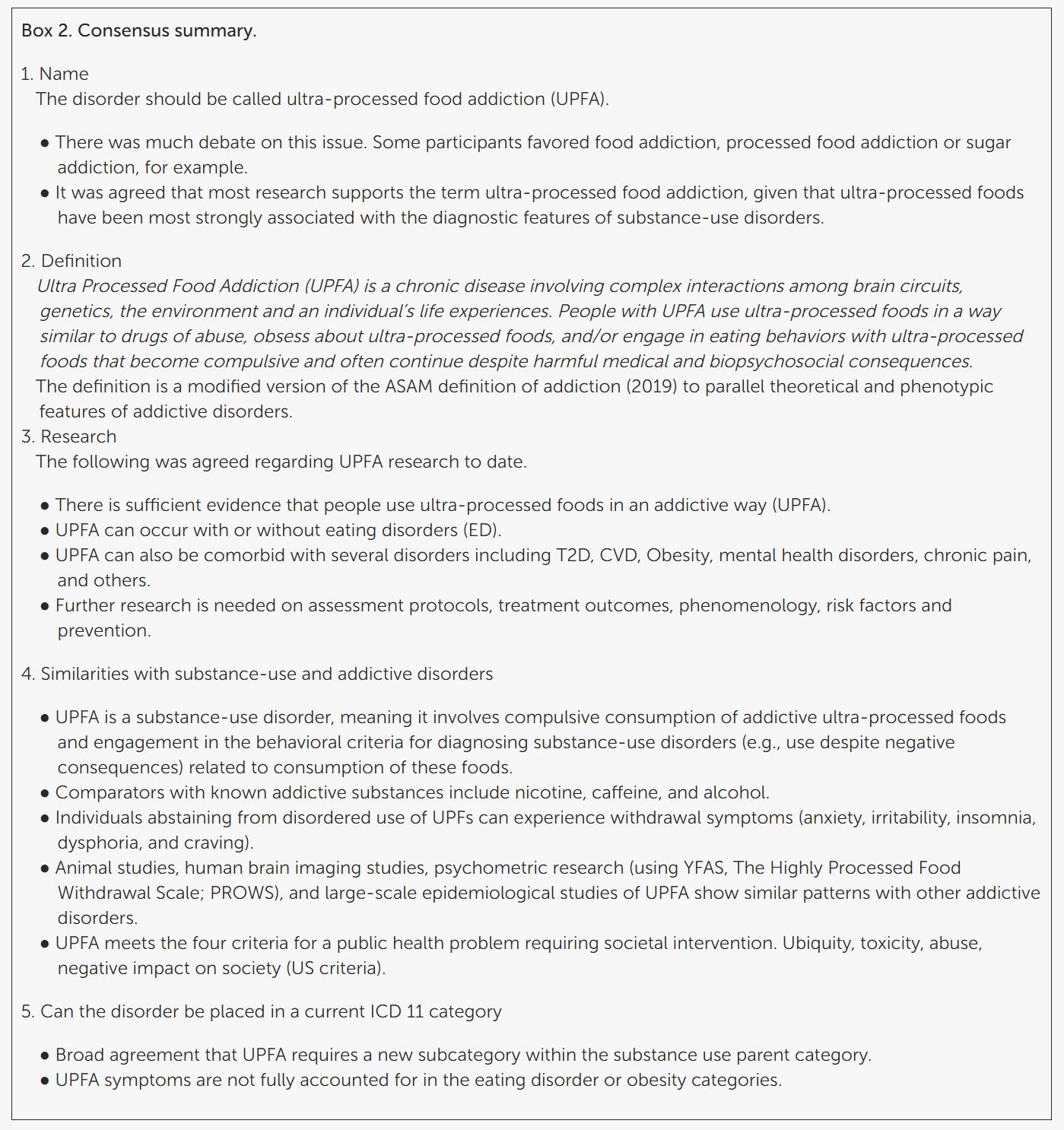

A consensus paper was published this year: Toward consensus: using the Delphi method to form an international expert consensus statement on ultra-processed food addiction [12].

FINAL AGREED CONSENSUS SUMMARY:

PSGR earlier, interviewed the lead author of that paper, Dr Jen Unwin in two amazing interviews:

Without support - health coaching and pathways to change often life-long dietary patterns - it can be extraordinarily difficult to reverse out of the food-dopamine merry-go-round that may be a key factor in driving the current (rising) levels of metabolic and mental illness across global populations.

But this work is key to turning the metabolic and mental health crisis around, and to preventing diagnoses in younger and younger populations.

PSGRNZ would love to interview Harvard trained psychiatrist Georgia Ede.

We’ve recommended her (excellent) book. After years as a conventional psychiatrist Ede transitioned to become a nutritional psychiatrist.

Eg. Podcasts and interviews:

or video: Best diet to improve mental health

Let’s just say - PSGR have more to say on this critical topic!

Stay tuned.

REFERENCES

[1] Yang Z, Zhang Y, Wu Y, Ouyang J. (2023). Factors influencing the starch digestibility of starchy foods: A review. Food Chemistry. 406:135009. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.135009

[2] Samuel VT, Shulman GI. The pathogenesis of insulin resistance: integrating signaling pathways and substrate flux. J Clin Invest. 2016 Jan;126(1):12-22. doi: 10.1172/JCI77812. Epub 2016 Jan 4. PMID: 26727229; PMCID: PMC4701542.

[3] Li, M., Chi, X., Wang, Y. et al. (2022) Trends in insulin resistance: insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 7, 216. DOI:10.1038/s41392-022-01073-0

[4] Samuel VT, Schulman GI (2012). Mechanisms for Insulin Resistance: Common Threads and Missing Links. Cell. 148(5):852-871. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.017.

[5] Lee SH, Park SY, Choi CS. (2022). Insulin Resistance: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. Diabetes Metab J, 46(1):15-37. DOI: 10.4093/dmj.2021.0280

[6] Flatt JP. Glycogen levels and obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996 Mar;20 Suppl 2:S1-11. PMID: 8646265.

[7] Kahn BB, Flier JS. (2000) Obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Investig. 106(4):473–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI10842

[8] Fazio, S., Fazio, V., & Affuso, F. (2025). The link between insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia and increased mortality risk. Academia Medicine, 2(2). DOI: 10.20935/AcadMed7786

[9] Wu, Y., Ehlert, B., Metwally, A.A. et al. (2025) Individual variations in glycemic responses to carbohydrates and underlying metabolic physiology. Nat Med 31:2232–2243. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-025-03719-2

[10] Lennerz B, Lennerz JK. (2017) Food Addiction, High-Glycemic-Index Carbohydrates, and Obesity. Clin Chem. 2018 Jan;64(1):64-71. DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.27353

[11] Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB (2019). Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutrition, 22(5):936–941. DOI:10.1017/S1368980018003762Ultraprocessed foods can layer on top of carbohydrate heavy dietary intakes that over time, form a carbohydrate burden, however ultraprocessed foods are most associated with food addiction.

[12] Unwin J, Giaever H, Avena N, Kennedy C, Painschab M and LaFata EM (2025) Toward consensus: using the Delphi method to form an international expert consensus statement on ultra-processed food addiction. Front. Psychiatry 16:1542905. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1542905

WELL DONE WITH THIS REPORT. AT MY LAST VISIT TO A DOCTOR I TOLD HIM THAT THE FUTURE OF MEDICINE IS FOOD.