The Precautionary Approach is outdated?

What a porky!

‘various reports over the past 15 years have found that the HSNO Act’s GMO provisions are increasingly out of date’

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employments’ Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) grandly stated that many provisions are out-of-date - including the use of a precautionary approach.

The justification was based on an oblique citation for ‘various reports’:

2 Including by the Royal Society, the Productivity Commission, and the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor

The Royal Society was never funded to assess the merits of the precautionary principle or principle. There is no mention on the Royal Society website, or in their gene technology promotional literature that the precautionary principle is out-dated.

PSGR have been unable to locate any evidence that the Productivity Commissioner claimed that the precautionary approach was out-of-date.

The Prime Minister’s Chief Science Adviser has never stated that the precautionary principle, or approach was outdated in any of their gene technology promotional literature. In 2019 and 2023 briefing papers by the Chief Science Adviser, there was no direct mention of the provisions listed by MBIE as being ‘out-of-date’.

HOW DID MBIE OFFICIALS COME TO BELIEVE THE PRECAUTIONARY APPROACH WAS OUTDATED?

(Information drawn from PSGR’s Hijacking Democracy Part 1 Paper.)

In a June 18 event briefing on a Meeting with the New Zealand Environmental Protection Authority MBIE proposed that removing the precautionary approach for risk assessments was based on ‘good regulatory practice’.

Where did the claim of being based on ‘good regulatory practice’ come from?

PSGR have been unable to source any document to provide a reasoning for this. We’re concerned it has been manufactured - out of thin air.

PSGR recognise that industry-aligned groups can lobby government officials to downplay the precautionary principle. However, the:

‘The Innovation Principle is complementary with the Precautionary Principle, as precaution and innovation are equally important.’

Regulation to protect human and environmental health can promote innovation.

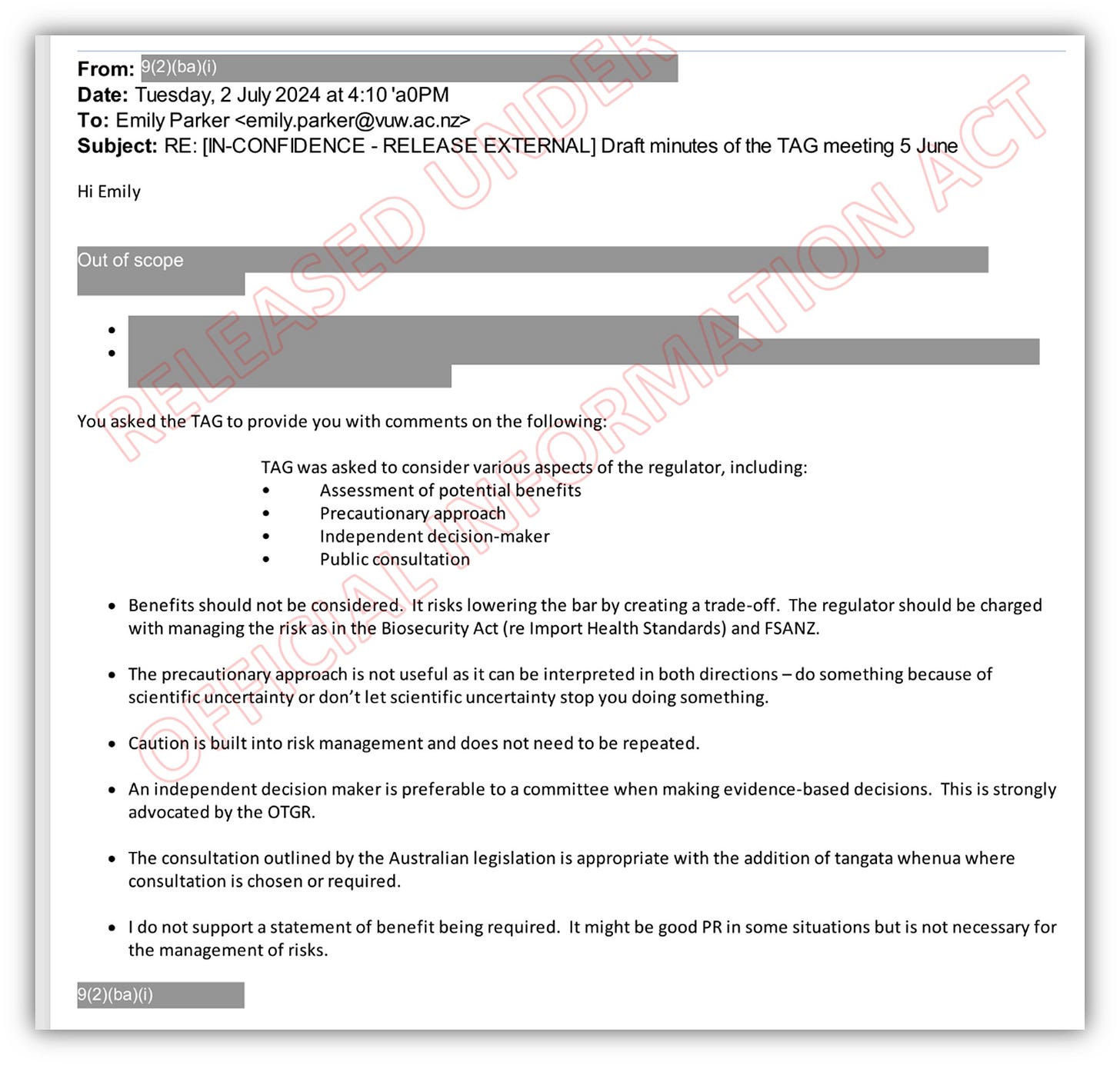

A November 2024 Official Information Act (OIA) request revealed that the Technical Advisory Group’s (TAG) consideration of precaution and the precautionary principle appeared to be rudimentary and exclusively based on information supplied directly by Simon Rae of MBIE to both the TAG group and the New Zealand Environmental Protection Authority.

The TAG had a limited role and a minor workload. The TAG broadly lacked independent experts in risk assessment regulatory reform and process (page 123).

Information to the TAG group which was approved by Simon Rae, emphasised that New Zealand wording was significantly more conservative than the internationally agreed definition of the precautionary approach. The TAG group were told that the HSNO Act definition was more conservative than the Rio Declaration text used in the Australian Gene Technology Act.

Rae’s explanation of the precautionary approach was exclusively couched in relation to Australian legislation. However, while the Australian legislation provides that officials may act where there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage and that full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures, no such content has been drafted into the New Zealand Bill.

The New Zealand Bill does refer to decision-makers having regard for the Convention on Biological Diversity ; and the Cartagena Protocol (s5 (a) and (b)). Having ‘regard for’ does not impose an obligation to take a matter into account. This includes a requirement to consider precaution and any requirement to act to prevent environmental degradation should there be a lack of full scientific certainty.

From the information that has been publicly released, on July 2, 2024 the TAG were provided with Rae’s advice and then asked to provide comments on the following extremely rudimentary statements:

Based on the response to DOIA REQ 0006467, no comments were then forthcoming from the TAG.

It appears that on the basis of MBIEs advice to the June TAG and NZ EPA meetings, that this provided sufficient information to agreed that a precautionary approach and ethics considerations were not required. No other analysis is publicly available.

MBIE appears to be communicating authority while contradicting and setting aside long recognised conventions and maxims that are required to underpin regulatory policy development so as to ensure that regulations do not benefit narrow interest groups.

The Government expectations for good regulatory practice manual recognises that any statement must be evidence informed. This has not occurred, and rather, as we see here, any narrative around precaution has been tightly controlled by MBIE officials.

MBIE also emphasised to the TAG that good regulatory practice focuses attention on operative mechanisms by way of setting a risk management framework or decision-methodology in secondary legislation. This bureaucratic language for claiming that the secondary legislation will contain the parameters which bureaucrats decide when a GMO is not a GMO.

‘The proposed legislative trigger for a regulated tier is products and processes that create outcomes distinguishable from conventional breeding. This trigger inevitably leads to future semantic disputes of what conventional breeding means, and technical challenges to distinguishability. These debates and contests aren’t focussed on safety and are not efficient ways to regulate.’[INBI (a)] [INBI (b)]

Yet the overarching purposes of an Act for a regulator, is required in place to shape regulatory approaches to risk management, and inform how any decision-methodology will be designed.

MBIE communicates to the TAG that the regulator will not have to make judgments that are inherently and unavoidably value based when regulatory decisions revolve around judgements on values. MBIE language suggests that all decisions will be exclusively technical.

MBIE have shown no interest in evaluating global regulatory practice, but have instead adopted a parochial perspective that seems to at once rely on Australian legislation, but then act to water-down and alter, even Australian laws.

This is evidenced by MBIEs ‘strict liability’ perspective which would reposition the bar for risk much higher than a precautionary approach based on an observed threat, but lack of full scientific certainty.

MBIE did not undertake a global assessment of best practice regulatory risk assessment, nor did it publish an in-depth paper to justify these claims. It appears that MBIE merely advised Ministers who had no option but to believe MBIE’s stated ‘facts’. The Post stated that:

‘Official documents from the Ministry for the Environment (MfE) from a meeting in June, chaired by Science and Technology Minister Judith Collins, say it was agreed the legislation should not include a reference to the precautionary approach and ethics should be excluded from consideration.’

In an In Confidence Paper dated August 29, 2024 (8/60), Minister Collins stated that she believed that ethics considerations were appropriately addressed in other legislation. Her focus did not concern broader societal values and the ethics of releasing a genetically modified potentially heritable gene, or gene designed to kill or maim, into the environment. Collins retained her consideration to narrowly focus on animal and human trials.

There is no critique outlining how officials came to the conclusion that precautionary approach/principle would be outdated and no longer ‘good practice’. No discussion documents appear to have been supplied to MBIE to consider these issues in depth. The RIS makes no mention of best practice.

There is a dearth of evidence to suggest that MBIE have assessed legislation in key trade markets to evaluate the extent to which principles and ethics - including precaution - are integrated in the equivalent legislation in these jurisdictions.

Ethics-based conversations have been repeatedly set aside by the government. The Royal Commission on Genetic Modification 2001 report recommended a three-pronged approach including the establishment of a Parliamentary Commissioner on Biotechnology, a Bioethics Council and a biotechnology strategy. None of these recommendations are in place in 2025.

MBIE obviously did not conduct a global review, but relied on claims to assert that the precautionary approach (Section 7 of the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996) was outdated.

We can ask - is the European Union then ‘out-dated’ - according to MBIE?

The European Union is a premium export market.

The precautionary principle is detailed in Article 191 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, page C 202/132 where it is mentioned once.

Union policy on the environment shall aim at a high level of protection taking into account the diversity of situations in the various regions of the Union. It shall be based on the precautionary principle and on the principles that preventive action should be taken, that environmental damage should as a priority be rectified at source and that the polluter should pay.

The European Commission further clarify in the document: Brussels, 2.2.2000 COM(2000) 1 final COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION on the precautionary principle that (page 3):

Where action is deemed necessary, measures based on the precautionary principle should be, inter alia:

proportional to the chosen level of protection,

non-discriminatory in their application,

consistent with similar measures already taken, based on an examination of the potential benefits and costs of action or lack of action (including, where appropriate and feasible, an economic cost/benefit analysis),

subject to review, in the light of new scientific data, and

capable of assigning responsibility for producing the scientific evidence necessary for a more comprehensive risk assessment.

PSGR MAKE ONE FINAL NOTE:

We ask you to search for government documents, and white papers outlining to officials how to employ a precautionary approach (as per S7 of the HSNO Act) in their duties, that might be published on the websites of government agencies who administer the HSNO Act and act under the powers of the HSNO Act.

If you find any, please share with PSGR.

PSGR haven’t been able to find any guideline documents to support officials in any work carried out under the HSNO Act - producing policy, developing guidelines or making decisions for risk assessment or approvals or re-approvals. The NZEPA’s Risk Assessment Methodology for Hazardous Substances (2022) publication does not provide any instructions for officials on how to apply a precautionary approach in risk assessment, and there do not appear to be any other guidance documents.

We might well ask why.

For more information on the Precautionary Principle please go to PSGR’s Precautionary Principle page.