Unsurprising move to increase residue levels by MPI

The bad news: MPI will increase the residue levels because they can. The good news: let's harmonise with Europe & get glyphosate off food & feed crops in New Zealand and Australia.

Ministry for Primary Industries: Submissions Are NOW Open – Here’s How to Have Your Say

Deadline: 5pm, 16 May 2025

Email: ACVM.Consultation@mpi.govt.nz

View the full consultation document here:

👉 Read the NZ Food Safety Discussion Paper (PDF)

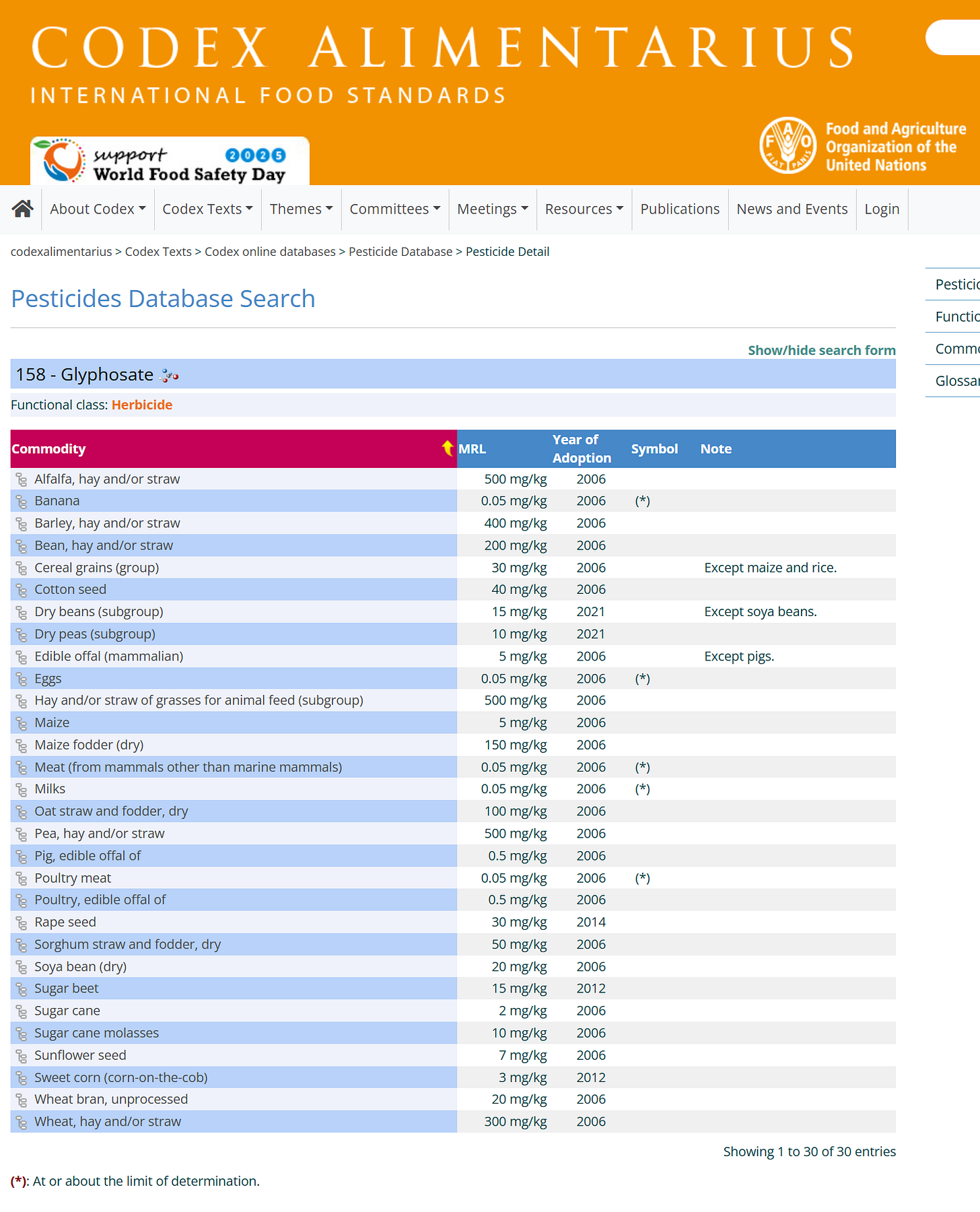

The Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) have proposed to increase the following residue levels for glyphosate:

Wheat, oats, barley: from 0.1 to 10 mg/kg

Field peas (dried): from 0.1 to 6 mg/kg

NB: PSGR make every effort to be accurate. If there is incorrect content in this article please advise us and we will update our information.

Here are the facts:

No New Zealand government authority has undertaken a toxicological study to evaluate the current evidence on safe dietary exposures for a lifetime.

No New Zealand government authority has reviewed the combined exposure risk from dietary, dermal and inhalation pathways in the past 3 decades.

New Zealand pretends that we have a similar glyphosate use profile as Europe, and therefore similar risks.

Bayer keeps losing court battles because courts find that glyphosate causes cancer in plaintiffs. Pesticide companies are now seeking legal immunity across U.S. states so that they can’t get sued when farmers and growers get cancer.

Europe differs from NZ practice in two major ways: Europe has banned the spraying of glyphosate on food crops, Europe doesn’t spray glyphosate down roadsides and in urban areas.

Our domestic ‘good agricultural practice’ GAP fails to address this variance.

New Zealand glyphosate permissions on crops: wheat, barley, oats and threshing peas. Spray 7-12 days prior to harvest when the grain moisture is less than 30%. Do not harvest within 7 days of spraying. Threshing peas, apply 7-14 days prior to harvest when pods have dried.

No New Zealand government authority seems to have an obligation or funding to evaluate safe dietary exposures.

No New Zealand government authority has assessed farmer or applicator exposures (dietary, inhalation and dermal).

MPI have created a health based guidance value of 0.27mg/kg without showing the underlying data. It approximates the old European level of 0.3mg/kg so they are theoretically in a safe zone.

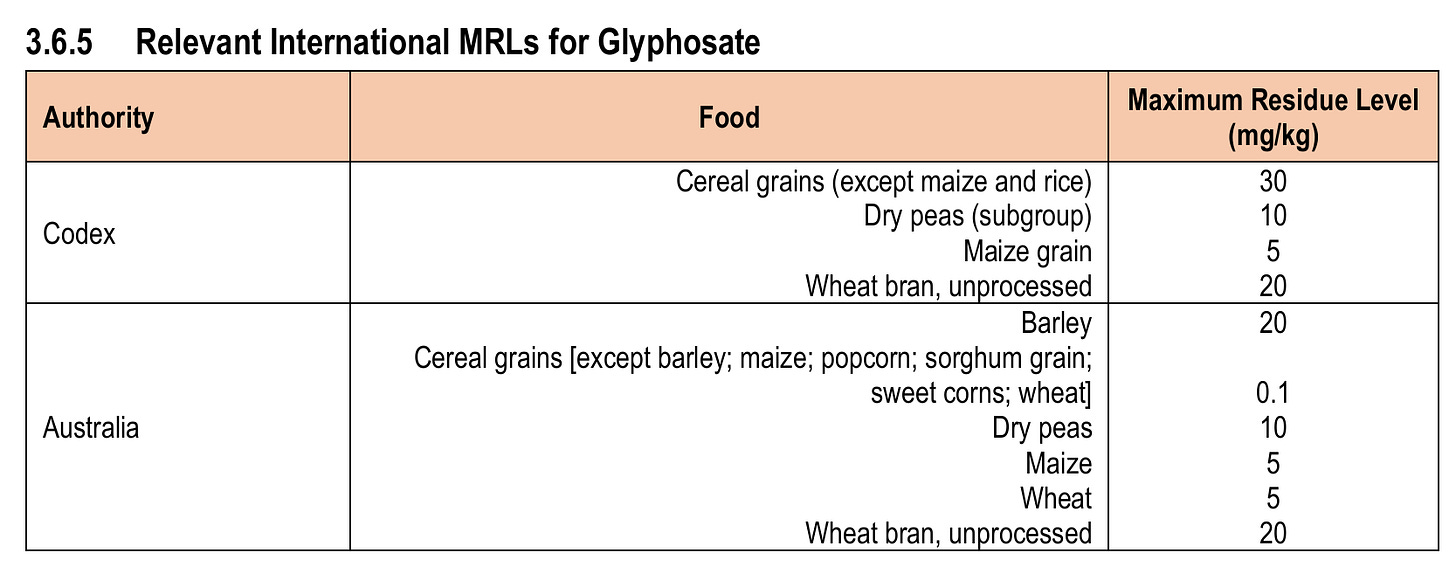

It is unlikely that nothing will shift MPI from increasing these levels because it will bring New Zealand into line with other global pesticides regulatory agencies. In reality - the new proposed maximum residue level (MRL) for wheat of 10mg/kg harmonises with Europe which is ‘best practice’ while the 6mg/kg appears to be under most (though Europe does not have a dried pea category): ‘To ensure the New Zealand MRLs will not unduly impact trade, the MRLs set by Codex and a selection of other international regulatory bodies are reviewed to evaluate trade risk.’

PSGR recommends:

New Zealand usage of glyphosate differs from best practice because it is sprayed on food and animal feed crops, commonly down roadsides, and in urban areas. This can stop.

MPI together with the NZ EPA TAKE ACTION to align with European agricultural practice and ban the overspray of glyphosate on human food and animal feed crops (to dry down or desiccate the crop before harvest).

New Zealand puts pressure on Australia to ban sprays of glyphosate on human food and animal feed crops. Most wheat used in the North Island of New Zealand is imported from Australia.

That MPI and EPA are transparent about the fact that they have never conducted formal risk assessment, and stop pretending that glyphosate on human food crops is safe for consumption if they have never undertaken a comprehensive risk assessment to understand New Zealand usage patterns and exposure scenarios.

Agencies must support research to shift away from herbicide dependence. We act to protect the health of our farmers and our agricultural soils. Integrative pest management and more investment in weed tech has an essential part to play to help reduce farmer dependence and transition away from glyphosate use.

MPI and EPA must be transparent about the fact that New Zealand has a growing problem around glyphosate resistance (Dr Trevor James and colleagues - wild carrot, ryegrass). This is a global problem and just using more tank mixes with additional herbicides and synergists simply make the formulation more toxic to farmers and consumers.

New Zealand recognise that Europe has embedded a stronger application of the precautionary principle in European legislation and that we can do this also.

NEW ZEALAND’S (ABSENT) DATA

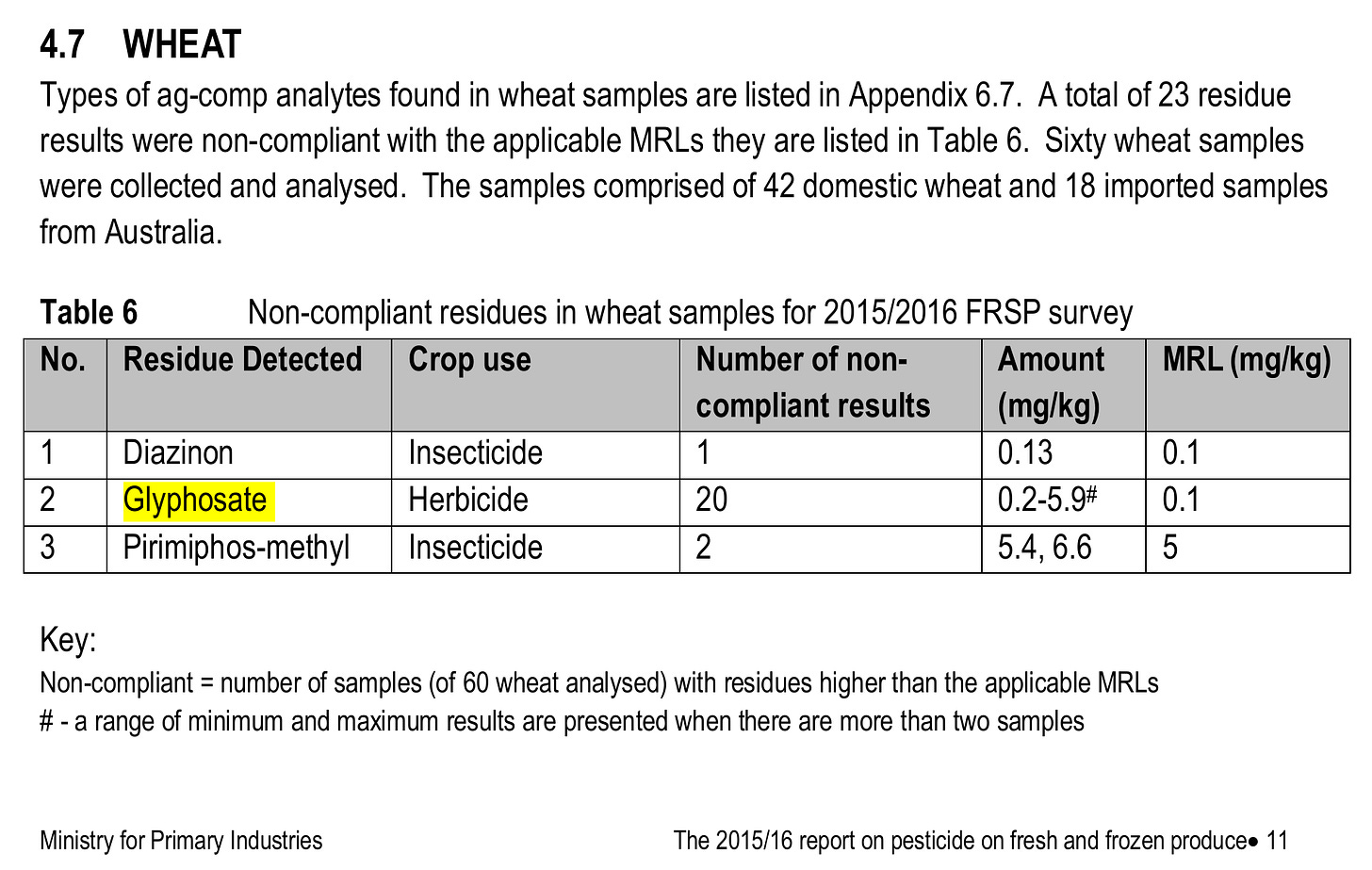

The current proposal to increase glyphosate levels are because detections are higher than the current maximum permitted residue level. In 2017 the Ministry for Primary Industries confirmed glyphosate residues were detected in 26 out of 60 wheat samples. Twenty of the samples contained glyphosate above the MRL of 0.1 mg/kg

There were 20 (out of 60) non-compliant wheat samples with glyphosate levels exceeding the New Zealand default MRL of 0.1 mg/kg (as glyphosate has no set MRL the default MRL applies). None of the wheat samples posed any food safety risks. MPI followed up with the 20 wheat farmers. As a majority of the wheat farmers were following label instructions, there could be other external factors and farming practice changes that may have contributed to the detected levels above the default MRL. MPI is now proposing a review of the residues information for glyphosate.

That review was never undertaken.

MPI do not appear to have conducted a formal dietary risk assessment for glyphosate. Searches on the website fail to identify relevant papers or guidelines. Instead of a transparent analysis this paper was released on March 17, 2025.

Proposals to Amend the New Zealand Food Notice: Maximum Residue Levels for Agricultural Compounds. New Zealand Food Safety Discussion Paper No: 2025/01. Ministry for Primary Industries.

The paper comes up with information that cannot be identified to be derived from legislation. No information on deriving a safe dietary exposure level appears to come from either the Food Act 2014, the HSNO Act 1996, or the ACVM Act 1997.

The HBGV of 0.27 mg/kg bw/d was considered appropriate for use in the assessment. Based on the residue profile expected in food from crops treated with glyphosate, and using the default MRL of 0.1 mg/kg for animal commodities, the NEDI is estimated to total less than 3% of the HBGV.

There seems to be no declared process for this. It is the age of dietary guidelines and the underlying data that is of concern. The dietary intake data is based on 3 decade old WHO guidelines:

This exposure is estimated by calculating the national estimated daily intake (NEDI) in accordance with the Guidelines for predicting dietary intake of pesticide residues (revised) [World Health Organization, 1997].

Dietary exposures for New Zealand are nearly 3 decades old:

The NEDI calculation uses the total residues in food derived from all New Zealand authorised uses of an agricultural compound, including all toxicologically significant residues, and regional dietary consumption data derived from the 1997 National Nutritional Survey for adults and the 1995 National Nutrition Survey of Australia for children. The calculated NEDI is then compared with the Health Based Guidance Value (HBGV) associated with the compound; if the total residues derived from all uses of the agricultural compound is estimated to be less than the HBGV, the dietary exposure is unlikely to pose a health risk to consumers.

Then we take into account the corporate studies that derive the so-called safe levels of glyphosate. But none of this really matters - what matters is simply the relevant international levels for glyphosate.

Codex Alimentarius residue levels are based on an ADI level of 1mg/kg bodyweight per day level that was derived from a 1993 Cheminova study and was set in 2006 by the WHO and FAO in their toxicological evaluations. The crops could then be sampled for residue levels, and reverse engineer levels to be under the ADI level, based on the proportion of daily dietary consumption of a particular food crop. While the toxicological evaluations can be updated, a keen observer will recognise that sequential evaluations will refer back to ADIs based on earlier evaluations.

NEW ZEALAND’S HAPHAZARD TESTING REGIME

Since 2014, we've done several tests for glyphosate residue in food:

Processed fresh milk and cream from retails – no residues detected (2014/15)

Raw milk – no glyphosate residues detected (2014/15)

Pea crops – no glyphosate residues detected (2015/16)

Wheat crops – no health or food safety concern detected with present glyphosate levels (2015/16)

Honey – no health or food safety concern detected with present glyphosate levels (2017/18, and 2018/19)

MPI refused to include glyphosate in the 2024 New Zealand Total Diet Study (Infants and Toddlers):

‘NZFS reviewed the IARC report in July 2015 (IARC, 2015) and concluded that IARC had done a hazard assessment and not a risk assessment.’

‘A number of countries such as Australia, USA, Canada, and more recently the European Union have either recently reviewed glyphosate, or have undertaken a risk assessment and have concluded that glyphosate is unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans. In the case of the European Union, it recently renewed its approval for 10 years from 16 December 2023.

NO RISK ASSESSMENT

The New Zealand Environmental Protection Authority (NZEPA) have refrained from conducting a formal risk assessment of glyphosate, for over three decades. MPI have ignored all court findings. The Environmental Law Initiative are taking the NZEPA to court - the hearing is scheduled for June.

NZ EPA’s regulatory risk assessment methodology does not provide instructions for risk assessment to include the combined risk to humans from dietary, dermal and inhalation exposures.

Instead of undertaking formal risk assessment the NZEPA evaluates substances on the basis of information available at the time of the application. The corporation provides toxicology and ecotoxicology studies. Instead of risk assessment, NZEPA staff review new data and compare it against old data provided by the exporting companies.

The Ministry for Primary Industries do not seem to have any form of guidelines to assess dietary risk in combination with environmental exposures.

Conventionally, acceptable daily exposures would be derived from a combination of oral (dietary), dermal and inhalation routes. These would be assessed in risk assessment by independent toxicologists with expertise in toxicology. They would look at everything from cellular effects (in vitro), to rodent or dog studies (in vivo) to epidemiological studies of populations.

For example, children might eat a lot of glyphosate sprayed wheat, and a little bit of glyphosate contaminated honey. New Zealand honey was turned back from Japan because glyphosate contamination exceeded Japan’s maximum residue levels.

MPI seem unaware of the fact that different foods have different contamination levels which accumulate. This August 21, 2020 honey example shows that MPI do not possess the expertise of toxicological scientists:

For context, a five year-old child who was consuming honey with 0.1 mg/kg of glyphosate residues (the default maximum residue level in New Zealand) would need to eat roughly 230kg of honey every day for the rest of their life to reach the World Health Organization Acceptable Daily Intake for glyphosate.

Beekeepers are very vulnerable to close proximity spraying, for example on pastures and food crops. Beekeepers are unlikely to complain to farmers as it can be difficult to secure good land to place beehives.

But the bigger work to understand dietary exposures hasn’t been done.

GLYPHOSATE’S SECRET UNPUBLISHED STUDIES

The acceptable dietary intake is one subset of the overall exposures. New Zealand has historically not done this work to set a acceptable daily intake based on New Zealand data, but rather refers to the WHO-FAO determinations, based on old unpublished industry studies.

For example, the drinking water ADI level of 0.3mg/kg bodyweight a day is based on a 1981 Monsanto study, first set in 1985, and the dietary ADI level of 1mg/kg bodyweight is based on a 1993 Cheminova study and was set in 2006

Bio/Dynamics Inc. (1981a) A lifetime feeding study of glyphosate (Roundup technical) in rats. Unpublished report prepared by Bio/Dynamics Inc., Division of Biology and Safety Evaluation, East Millstone, NJ. Submitted to WHO by Monsanto Ltd. (Project No. 410/77; BDN-77-416).

Atkinson, C., Strutt, A.V., Henderson, W., Finch, J. & Hudson, P. (1993b) Glyphosate: 104 week combined chronic feeding/oncogenicity study in rats with 52 week interim kill (results after 104 weeks.). Unpublished report No. 7867, IRI project No. 438623, dated 7 April 1993, from Inveresk Research International, Tranent, Scotland. Submitted to WHO by Cheminova A/S, Lemvig, Denmark.

Glyphosate. Joint FAO-WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues. Pesticide residues in food – 2004: Part II toxicological evaluations. Report No. WHO/ PCS/06.1. Geneva. ISBN 978 92 4 166520 9. WHO published 2006 p. 160

MPI are raising maximum residue levels in cereals and peas because they can.