Deregulation of genetically modified/engineered/edited organisms is in the media - but there is another consultation no-one has heard of. It involves our food safety authority proposing (P1055) to declare a wide range of gene-edited foods as substantially equivalent to conventionally bred foods.

(NB. genetically modified or engineered, or gene edited are all interchangeable terms).

Food Standards Australia New Zealand’s (FSANZ) new proposal will have the effect of give a status of non-GMO to a wide range of food products -

• a single outcomes-based definition for genetically modified food;

• a definition based on the presence of novel DNA in the genome of an organism, instead of foreign DNA;

• revised definitions for novel DNA and novel protein;

• explicit exemptions for food derived from null segregant organisms and grafted plants;

• explicit exemptions for substances regulated by other standards in the Code (food additives, processing aids and nutritive substances);

• an explicit exemption for substances used in cell culture to support the growth and viability of cells, and to process cells, for the production of cell-cultured food.

FSANZ notes it is a ‘paradigm shift’.

the overall effect of the new definition of GM food would be to reframe the regulatory approach to GM food, where food is proposed to be considered GM food based on the presence of novel DNA in the genome of the organism or cells from which food is derived. This represents a change from the current approach where food is considered to be GM food if it is derived using gene technology, irrespective of the outcome of that genetic modification process.

FSANZ appears more concerns with achieving clarity on the proposed definition, rather than seeking to understand a weight of public opinion. With this perspective, issues mentioned here are likely to be outside the scope of the consultation.

Current GMO risk assessment approach is case-by-case & process-based.

If a food is derived (and patented!) using gene editing processes - this triggers regulation. Regulation of technology in relation to airlines, chemicals, cars etc is common and important.

UNDERMINING PUBLIC CHOICE?

FSANZ new proposal contradicts consumer concerns and historic wariness around GMOs (there is a long history of financially incentivised food fraud and adulteration). This also ignores the position of exporters who trade on trust and GMO-free status. Demand for GMO-free food brands is higher than non-GMO, and consumers will pay a premium for GMO-free.

FSANZ is responsible for food safety, but they are proposing to ‘disappear’ a wide range of food (including processed ingredients), that they claim is low-risk, so that it could not be categorised as GMO. The impact is that people would effectively have no choice.

FSANZ’s proposal has not considered that research consistently finds that people will pay a premium for GMO-free food. E.g. · Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, French and American people prefer food that has not been genetically edited/modified. Studies tend to highlight social values, institutional trust, and awareness as important factors in public decision-making. There is expected societal opposition to eating gene edited/modified meat, where price discounts are insufficient to alter public attitudes.

FSANZ know that consumers have low-trust in gene edited food. They also know that people trust FSANZ. So why does FSANZ seek to ‘disappear’ products that are very much a product of genetic modification - because they’ve been patented by the corporation?

Proposal P1055 - Definitions for gene technology and new breeding techniques.

DEADLINE 10 SEPT:

One more week SEND IN YOUR RESPONSE TO FSANZ’S PROPOSAL

The FSANZ has refused to grant an extension, stating the timeline is standard.

Please note: consultation questions can be hard to navigate.

Warning: Neither mainstream nor farming media have advised the general public of this current consultation.

FSANZ aims to deregulate a large range of patented foods that have been genetically modified using new gene editing techniques (called precision breeding, new breeding, and new genomic techniques).

An earlier 2021 consultation has since been redrafted. (PSGRNZ response here).

FSANZ have a list of similar decisions globally. Please note Europe, who have been more conservative, have not finalised their regulations. Can NZ pause and identify best and safest practice?

FSANZ Consideration of costs and benefits paper fails to discuss consumer preferences for non-GMO food. No benefits are proven - see term ‘may’.

Australia and New Zealand have strong biosecurity rules, however biosecurity concerns where modified organisms could impact off-target organisms are not addressed, despite the fact that GMOs can be deployed at scale and pace.

Why is FSANZ happy to reregulate, but not discussing/consulting or updating technologies to predict unanticipated or off-target risk? (Example here).

Note that FSANZ prioritise innovation (Kollman et al. 2020) and cite papers that speculate that NBTs as useful tools, ‘may’ lead to improvements. Brookes and Barfoot 2020, Qaim 2020, Kovak et al 2022. Does this warrant this ‘paradigm shift’

FSANZ STATES ‘A PARADIGM SHIFT’ IN REGULATION

NB: ‘New breeding techniques’ (NBTs) (US and Australian terminology) and ‘new plant variety’ (US); in the UK ‘precision breeding’ - to Europe’s clearer and more transparent ‘new genomic techniques’ (NGTs).

‘Proposal P1055 represents a paradigm shift (p.39) away from the process-based understanding and regulation of gene technology used in food production to an outcomes-based approach. While consumers generally have quite low levels of awareness and knowledge about NBTs, it appears that current understandings tend to align more closely with a process-based 40 approach. Consumers tend to see food produced with NBTs on a spectrum with food produced using GM, rather than as being equivalent to conventional food. As a result of this process-based understanding, although not a top-of-mind food safety issue, a substantial proportion of consumers remain concerned about the long-term impact of these technologies on the environment, humans, animals, farmers’ livelihoods and conventional food varieties.’

The irony:

The reason FSANZ is established - the legal purpose of FSANZ, is to protect public health, and maintaining trust in the quality of food consumed here and exported.

FSANZ are downplaying the uncomfortable truth that consumers identify both older and newer genetic modification/engineering/editing techniques as being on a spectrum.

The terminology is confusing and obscures the effect that DNA can be altered with the organism then being patented by the corporation.

Molecular biologist Professor Jack Heinemann recently shed light on the contradictions:

GMOs are defined as organisms with a novel combination of genetic material created using gene technology. This can be done by adding (eg transgenes), changing or removing (eg null segregants) DNA sequences to create novel combinations and new traits.

Suggesting that GMOs are only organisms with added DNA lures the government into thinking there is a class of “low-risk gene-editing activities” when they’re not used to add DNA, and these “can be exempted from regulations”.

Does the P1055 contradict their obligation to protect food?

The effect of the P1055 consultation would be that a wide range of foods would escape GMO/GE nomenclature and not have to be labelled as a genetically modified (or edited organism.

In a FSANZ 2022 Consumer Survey: Nearly half of respondents had some level of concern regarding GM food. When asked directly about concerns regarding GM foods, 46.7% of respondents indicated they had some level of concern. Key concerns about GM foods were safety to humans, the trustworthiness of GM producers or scientists, environmental impact and animal welfare.

This is a PSGRNZ discussion with:

Elvira Dommisse, BSc (Hons), PhD, former scientist, Crop & Food Research Institute (1985-1993), working on GE onion programme,

Jon Carapiet MA, MPhil, Senior Market Researcher, Trustee PSGRNZ

Jodie Bruning, B.Bus.Agribusiness (Monash Australia); MA Sociology (Research)

PSGRNZ’s 2023 paper: Deregulation? Biotechnology & gene editing: New Zealand context.

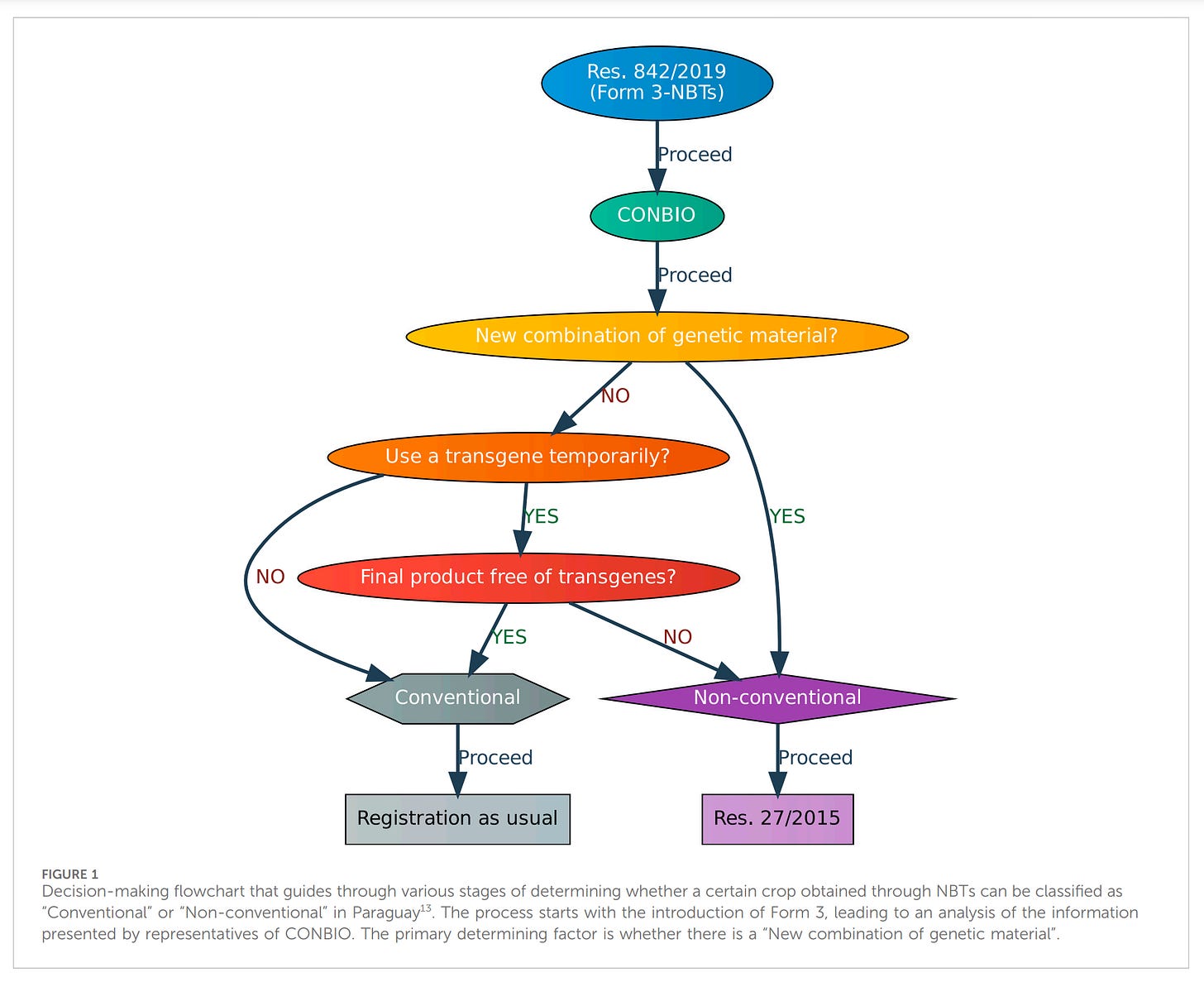

Example of a regulatory decision-chart from Paraguay.

If the final product is free from transgenes it is conventional, even if gene editing has been used extensively (the company then owns the patented organism):

The power to assess and declare an NBT sits with the corporate applicant.

The FSANZ current proposal echoes the responses from corporate industry and biotechnology developers, made in the first round of consultations. (See from page 49 onwards. In the first round, FSANZ broadly disagreed with the points made by public interest organisations, including PSGR:

FSANZ does not agree however that “rigorous independent testing” of the type specified by the submitters is either necessary or appropriate to establish the safety of a food.

…

FSANZ considers it unnecessary and also impractical to undertake post market surveillance of NBT foods. FSANZ notes such surveillance is also not undertaken for existing approved GM foods.

…

FSANZ undertook a comprehensive safety assessment which supports the exclusion of certain NBT foods from pre-market assessment and appoval as GM foods. This is because such foods are considered to be as safe as conventional food.

…

the scientific literature shows us that a large number of substantial genetic changes (both natural and induced, intended and unintended) have occurred or have been introduced to organisms using conventional methods. Despite these significant changes to genomes, food derived from these organisms has a long history of safe human consumption. There is overwhelming scientific evidence to support FSANZ’s conclusion that conventional food with a history of safe use is an appropriate benchmark against which to compare other foods.

RISK THAT SCALES - BIOTECHNOLOGY

FSANZ does not discuss risk that arises when editing tools can scale up changes, and the speed of deploying/marketing products onto the market and into agriculture vastly outpaces and potentially harmful genetic change that could occur via slower natural or breeding processes.

Share this post